The world is not on track to achieve the Paris Agreement temperature targets, and low carbon investing in isolation is unlikely to change this. The magnitude of the environmental crisis facing our planet requires that allocators take bold and creative action. In this paper we set out the case for supplementing a low carbon approach with an environmental solutions strategy, which we believe will grant investors access to the biggest structural growth opportunity of a generation.

At TT International we understand the pressure that asset allocators face from their stakeholders to deliver portfolios that are impacting the world in a positive way. Underlying asset owners increasingly demand portfolios whose environmental credentials are superior to those of peers and the market, that are advancing the decarbonisation process, and that are aligned with net zero ambitions.

There are various ways to approach environmental investing in order to achieve these goals. Perhaps the most common are:

- Low carbon. Investing in companies that have carbon-equivalent emissions which are below the benchmark and peers, that are aligned with achieving a net zero goal, or that have science-based targets to help achieve the Paris Agreement targets.

- Improvers. Investing in companies that are currently not low carbon, but which have demonstrated a firm commitment to become so, either through their operational actions or via other pledges.

- Sinners. Investing in companies with poor environmental profiles, which can then be encouraged through active engagement by equity owners to improve their behaviour.

- Environmental solutions. Investing directly in the companies that are producing the goods, services and systems that will ultimately enable the planet to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve biodiversity.

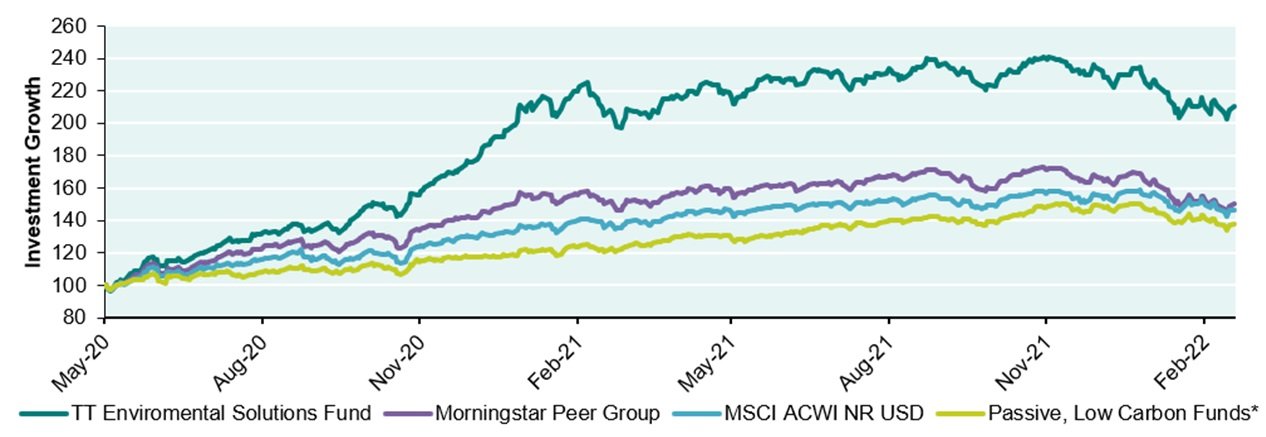

Ultimately that is why we launched the TT Environmental Solutions Fund. Our goal was to develop a novel approach to ‘impact’, which can get misrepresented in conventional environmental strategies. In addition to the better-understood aspects of ‘impact’ with regard to climate change, the strategy also focuses on the equally pervasive environmental threat of biodiversity loss. Moreover, it invests directly in the companies that are producing the goods and services to deliver the green transition. As a species we need to fundamentally change the way we generate energy, travel, grow our food, clothe ourselves, and construct our buildings. There is a revolution coming over the next 20 years that we believe represents the biggest structural growth opportunity of a generation. Many of the areas in our investment universe could realistically be 10-100 times larger in a couple of decades, providing exceptionally fertile ground for stockpickers. Put simply, we expect the strategy to have a high environmental hurdle for inclusion and to deliver high alpha, which it has achieved since inception:

* Aggregated, asset weighted performance of 5 largest low carbon passive funds on Morningstar, total $31.9bn in assets

Source: Morningstar, 28th February 2022, net of fees, USD

So why do we believe that a low carbon portfolio should be supplemented with an environmental solutions strategy such as ours?

1. The moral dimension

The first reason relates to the moral dilemma that we all face when allocating capital from an environmental perspective. This stems from the fact that there is a finite carbon budget remaining if we are to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels – an important threshold that would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change. The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report estimates that this budget is 440 billion tonnes. Since we are currently emitting 35 billion tonnes of carbon per annum, and this number continues to grow, it is clear that time is running out. As with any other finite resource, financial markets should be assessing which companies are most deserving of this remaining budget, and allocating capital accordingly. If markets were behaving efficiently, the companies that are having the biggest positive impact on the planet should be rewarded with a lower cost of capital. This raises the question: how do companies currently attract capital by qualifying for inclusion in a typical low carbon/net zero 2050 portfolio?

A – Business model. Unsurprisingly, the top constituents of many low carbon portfolios are companies whose business models are naturally not carbon intensive. This favours entities such as financials, software companies and experiential businesses, which of course only represent a small portion of investment opportunities across the world. Consequently, these portfolios often exhibit a heavy factor bias towards high-growth, asset-light business models, frequently in the Technology sector, and usually trading on high multiples. Moreover, whilst these companies might have low carbon footprints now, this does not necessarily mean that they are demonstrating improvement and will be net zero in the future. It is also important to question whether certain uses of carbon could be considered ‘luxurious’ or unjust in the context of the limited remaining budget discussed above. For example, Netflix might appear in a low carbon portfolio because of its relatively small footprint, but given its trivial product offering from an environmental perspective, it could be argued that Netflix should in fact already be net zero, and that companies producing the goods and services that will actually deliver the green transition are far more deserving of attracting capital.

B – Offsets. Companies can also feature in low carbon portfolios because they have committed to offsetting their emissions in some way. We believe this is sub-optimal for two reasons. Firstly, it is biased towards companies with extremely large balance sheets and high profit margins that enable them to effectively pay the penalty for polluting. More importantly, there is not an infinite opportunity for offsetting. Just as with carbon emissions, our planet only has the capacity to absorb a certain amount before problems occur. Taking this concept to the extreme, consider Shell. To offset just 35% of its emissions, the company says it would need to plant forests covering 28 million hectares – roughly the same size as Italy – by 2035. Offsetting on this scale would have negative ramifications for food production, forest quality, and the monocultures that would be created. Because of these issues, we believe that offsetting can only ever be part of the solution, and that the planet’s remaining capacity for offsetting should be directed towards the companies that are most deserving. Again, in our view these would be the companies which are using carbon to produce goods and services that will ultimately reduce emissions and improve biodiversity.

C – Luck. Low carbon portfolios are also likely to favour those companies that have the opportunity to produce their goods and services in the lowest emission environments. For example, Norwegian aluminium producer Norsk Hydro is able to source 70% of its energy renewably, compared to around one-third for its peer group. Simply because of its location in Norway, the company is a superior aluminium producer from a carbon perspective than Hindalco in India or Chalco in China. But this raises a question: is it optimal to allocate capital towards companies simply because they happen to be situated in areas where they benefit from renewable energy? It could be argued that companies such as Hindalco and Chalco, which are always likely to exist because national governments want to have localised supplies of such materials, are more deserving of a lower cost of capital if they are looking to fund investments that enable them to increase their renewably sourced energy.

D – Improvers. Companies can also be included in low carbon portfolios if they have demonstrated a commitment to reducing their carbon intensity. This certainly seems to be a legitimate way of allocating capital; it rewards companies that have invested to change themselves for the better, and research has shown that it is a particularly alpha-rich seam to tap. However, in order to be included in typical low carbon portfolios, these companies will often still need to have a low carbon footprint today. This tends to be as a consequence of the other three factors outlined above, which as discussed appear to be based on flawed rationale. Even if companies are included in low carbon portfolios purely on the basis of improvement, this often simply means promises of enhancements in the future as opposed to tangible improvements that have already been achieved. For example, we recently attended a presentation on an ESG improvers strategy for which having a commitment to adopt Paris Agreement targets in the future was sufficient to be included within its investible scope. Frankly, most companies we meet struggle to accurately forecast their earnings in 12 months’ time, let alone their carbon emissions in 2050, particularly when much of the estimates are predicated on novel technologies or offsets. Moreover, the notion of improvement varies substantially by company. UK supermarket Sainsbury’s aims to be net zero in Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 2040 through offsetting, whereas Microsoft aims to be carbon negative according to Scope 1, 2 and 3 by 2030. Because of these variations and forecasting issues, we believe that if companies are to be included in a low carbon portfolio on this basis, it should be because of demonstrated improvements rather than promises thereof.

Rewarding companies with a lower cost of capital based on having a low carbon footprint therefore seems less morally clear than it initially appears. Crucially, even if one were to disagree with all the arguments made thus far, the unfortunate reality is that the current low carbon investing approach is not sufficient; the world is not on track to achieve the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals.

It is time to adopt a new approach. Although we are all capitalists and believe that capital allocation based on price signals is optimal, for most of human history finance has not been the dominant model for allocating social goods. Time-honoured alternative models such as religion, philanthropy and communitarianism continue to coexist alongside capitalism, certain aspects of which are relevant for environmental investing. As much as we may believe that markets operate without moral influences on them, and that capital should be allocated wherever the return is highest, when it comes to environmental investing it is also important to consider the concept of justice and which companies are most deserving of our capital, given the planet’s limited remaining carbon budget. In our view, the optimal allocation of this budget is toward companies that are using carbon to build the products, services and systems that we will all need to live in a more sustainable way. It follows that capital should be allocated to these companies in order to reduce their cost of investment when scaling up solutions. This adds yet more weight to the argument that a low carbon approach should be supplemented with an environmental solutions strategy, particularly because an exclusive focus on low carbon investing ignores the bigger picture and leads to unintended consequences. We will now explore both of these concepts in further detail.

2. Not seeing the wood for the trees

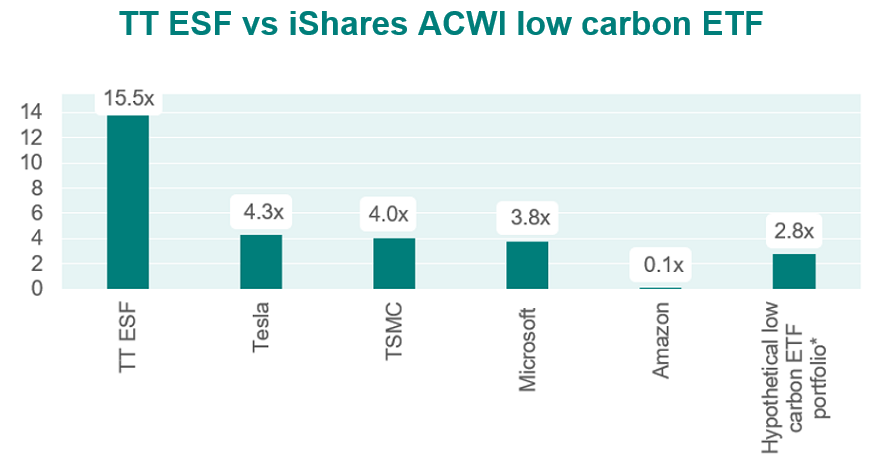

A – Carbon return on carbon employed. If the challenge is to build a sustainable world with the remaining carbon budget then carbon emissions are a one-dimensional way of looking at the problem that risks missing the wood for the trees. In finance we are used to the notion that spending capital has a cost associated with it, so if we choose to deploy it, we need to generate the highest possible return. We need to move to this way of thinking about carbon; ideally we would not use up the remaining budget, but if we do it is vital to get the biggest ‘bang for our buck’ in terms of building out the green infrastructure of the future. Importantly, environmental solutions companies typically have far higher ‘carbon returns on carbon employed’ than simple low carbon companies. One example is renewable insulation producer Rockwool, which we own in the TT Environmental Solutions strategy. Its manufacturing process is very energy intensive as it involves cooking and spinning rock, but the net carbon benefit is enormous. Over the product’s life cycle, it saves 100x the carbon used to produce it. In fact, the estimated ‘avoided emissions’ of TT’s Environmental Solutions strategy are typically over 15x higher than its actual emissions. The real figure is likely to be significantly greater as only half our investee companies currently report their avoided emissions, yet this number has been compared to the carbon emissions of the entire portfolio. In stark contrast, the avoided emissions of popular low carbon stocks Tesla, TSMC, Microsoft and Amazon are just 2.8x their actual emissions. These companies are the only ones in the top 10 of the iShares ACWI Low Carbon ETF that currently report their data. Crucially, because environmental solutions companies are investing in technologies that are likely to experience rapid growth over the next two decades, having a higher carbon return on carbon employed should go hand-in-hand with having a higher return on capital, both for the companies and their investors.

* Hypothetical portfolio based on investing in the 4 equally-weighted ETF companies that disclose avoided emissions.

B – Biodiversity. Another critically important aspect that gets missed by having a narrow focus on carbon emissions is the equally pervasive planetary threat of biodiversity loss. Indeed, the current extinction rate is running at between 1,000-10,000x the baseline level of extinction throughout human history, with devastating consequences for the world. We need to start thinking in a systemic, holistic way as the planet does not have distinct problems with carbon emissions, biodiversity, agriculture, water, plastics and so on, it has one overarching problem: the way we treat the environment. To illustrate the symbiosis that exists between carbon and biodiversity, consider the following examples from both land and sea. Whales are responsible for 1.7 billion tonnes of carbon sequestration activity annually, yet their population has fallen 60-90% over the last 100 years. Elsewhere, a study was undertaken in Yellowstone, a National Park in North America, after wolves were reintroduced there. The presence of these wolves meant that deer which had been grazing next to the rivers had to move higher into the hills, away from open territory. Without the deer to destroy saplings, trees began regenerating next to the river banks. The more shaded, cooler rivers became far more favourable environments for salmon, which were better able to spawn. More salmon rich rivers drew bears and eagles, the former of which can eat a remarkable 700 salmon in a day. After consuming and defecating the salmon by the river, levels of marine nitrogen increased substantially, allowing birch trees to grow 3 times faster than in other areas that did not have exposure to additional marine nitrogen. As they photosynthesised and grew, these trees sequestered carbon. As a result, the carbon intensity of the landscape was significantly enriched through a biodiversity solution.

It is clear that carbon emissions and biodiversity are inextricably linked, and we need investment approaches that reflect this. By narrowly focusing on emissions, we could solve the world’s clean energy problems and still destroy the planet; we would turn a carbon problem into a biodiversity issue. Without biodiversity, even if we could make the world a perfect temperature it is unlikely to be worth living in. For this reason, we believe that biodiversity issues should fall within an environmental portfolio.

C – Impact of capital. The final element that can get missed by exclusively low carbon investment approaches is the impact of our capital. As mentioned above, we are not currently on target to meet the Paris Agreement temperature goals. In order to change this, the technologies that will drive the green transition need to be developed and scaled across multiple areas, from electrolysers, EVs and solar panels to wind turbines, fuel cells and recycling facilities. Investing in a pure low carbon approach is highly unlikely to help these technologies scale up. In fact, allocating to a low carbon strategy or many of the companies that feature in those indices will only serve to further reduce the cost of capital for companies that already have such a capital surplus and uninspiring investment opportunity set that many of them are extremely net cash. In stark contrast, a lot of the companies that are building the green technologies of the future have a strong need for capital. They are regularly coming to the market in primary capital raises. This appears to be an egregious misallocation of capital which is directly undermining efforts to move towards a green future by choking the companies looking to build it.

3. Unintended consequences

We also believe that there are many unintended consequences of tackling environmental investing through pure low carbon approaches.

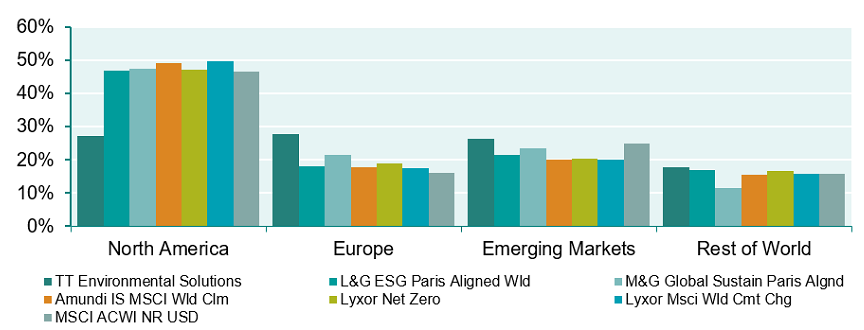

A – Investors are missing out on opportunities in Emerging Markets. Most low carbon approaches are heavily weighted towards the US, with relatively limited exposure to Emerging Markets. As such they completely miss many of the world’s most cutting-edge environmental technologies. For example, over 90% of the global solar value chain sits in China and East Asia. Korea produces two-thirds of the world’s battery cells, which means that much of the battery materials supply chain is also being localised in the country. Taiwan meanwhile, by virtue of its leading expertise in the semiconductor and electronics industries, is a key beneficiary of the electrification of the planet. If you were to distil the green transition into its simplest form, it is essentially a shift from hydrocarbon molecules – coal, gas and oil – to electrons. Taiwan is home to numerous companies in the supply chains for the electrification of homes and vehicles. As such, its economy is one of the most geared to the accelerating shift towards electrification. Not only are some of the most exciting new environmental technologies being developed in Emerging Markets, but also many of the world’s most valuable renewable energy resources are located in the global south. Whether it’s onshore wind in Brazil that blows as fast as offshore wind in the northern hemisphere, or first-class solar resources in South Africa and India, Emerging Markets have a huge abundance of natural resources to equip them for the energy transition. Crucially, many of these countries also have immature energy infrastructure networks. This means that they have an enormous opportunity to skip a level of development when they are building out their networks, bypassing many of the traditional hydrocarbon-heavy layers, and moving straight to distributed renewable energy and hydrogen. For these reasons, we believe that Emerging Markets should be a large portion of an environmentally focused portfolio. As can be seen below, the TT Environmental Solutions Strategy has a far higher exposure to Emerging Markets compared to a typical low carbon strategy. To help in this regard, the strategy leverages the expertise of TT’s market-leading EM team.

Source: Morningstar, 28th February 2022, net of fees, USD, primary share class used.

B – Index and ETF issues. As can be seen from the first chart in this paper, the volatility of the TT Environmental Solutions Strategy has not been materially different to that of passive funds, despite the alpha generation being significantly higher. We believe this could be partly because of a lack of active factor control in passive funds. Rather than dynamically assessing factors such as growth, yield, momentum and volatility, then adjusting exposure accordingly, passive funds are essentially providing consistent exposure to mega-cap Growth stocks throughout the market and economic cycles. Active managers have the ability to build portfolios that are diversified by factor, geography and thematic. They also have the flexibility to adjust the portfolio to changing risks and opportunities in the market, which can reduce volatility for investors. Moreover, many low carbon approaches – both active and passive – appear to have largely the same major holdings. Time and again the same names are present in the top 10 holdings: Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Tesla, Meta, TSMC, Infineon, Johnson & Johnson, and JP Morgan. Consequently, these strategies do not appear to be providing much diversification away from a standard global benchmark.

C – Harmful business models. Somewhat paradoxically, many of the biggest holdings in low carbon portfolios provide consumer products or marketing therefore – business models that are often actively hostile to the environment as they encourage excess consumption. Investors are therefore getting exposure to businesses that are simply not aligned with what they are trying to achieve. This goes back to our point about the misdiagnosis of the problem. These companies may well have a low carbon footprint, but they are unlikely to be driving the shift towards a sustainable future, and in many instances their business models are fundamentally harmful to the environment and biodiversity.

D – Distorted capital allocation. The final point on unintended consequences relates to the asset management industry more generally as opposed to specific low carbon approaches. Increasingly investors are requesting that their managers reduce the carbon footprints of their portfolios. The inadvertent issues that this can cause are perhaps best illustrated with a hypothetical example, albeit one that we have anecdotal evidence of. After being pressured by investors to lower their fund’s carbon footprint, a Portfolio Manager identifies their top carbon emitters and sees steel, cement, fertiliser, gas and oil companies amongst those names. They need to reduce their carbon footprint, but their performance is also measured against a benchmark that has significant energy exposure. Consequently, they are unlikely to sell their energy names, choosing instead to cut the names that have a high carbon footprint, but which are negatively correlated to energy such as fertiliser and chemicals companies. This leads to them selling companies that in many cases are making investments to reduce their carbon footprint, using the proceeds to buy companies that are supplying oil and gas. Such actions were surely not what was intended by the investor when they asked for the portfolio’s carbon footprint to be reduced.

For all the reasons discussed above, we believe that low carbon can only ever be part of the solution, and that a holistic approach to environmental investing is required, particularly as this allows investors to access arguably the biggest alpha generation opportunity of the next two decades. We therefore strongly advocate supplementing low carbon portfolios with environmental solutions strategies such as TT’s market-leading offering, which you can learn more about here.

Nothing in this document constitutes or should be treated as investment advice or an offer to buy or sell any security or other investment. TT is authorised and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).