TT takes a trip around the world to explore where clouds of uncertainty are gathering on the horizon.

"You pay a very high price in the stock market for a cheery consensus."

Warren Buffet

Herd mentality is one of the most powerful human instincts. As a species we take great comfort from treading the same path as others have walked before, and nowhere is this more evident than in the field of investment. Most investors are simply unable to ignore the consensus when making investment decisions, often for no other reason than because ‘being out there on your own’ means considerable career risk. Thus, when the majority of investors are in agreement, it inevitably rouses one’s inner contrarian.

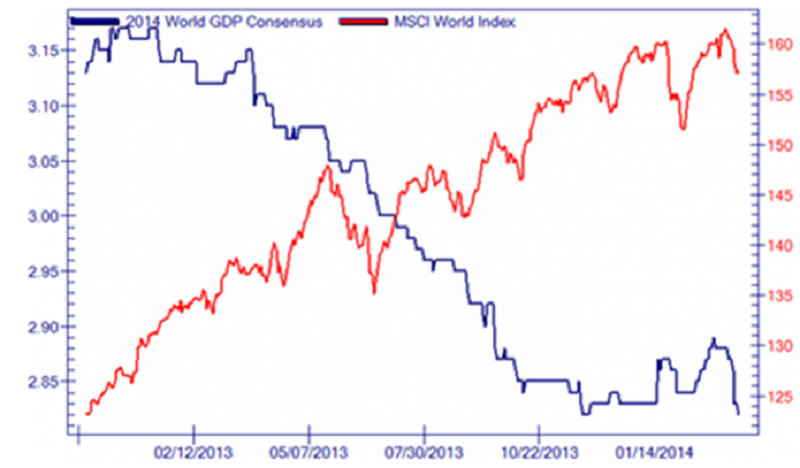

The consensus for 2014 is overwhelmingly positive for equities. Optimists argue that the US and Europe are gradually recovering, Japan is successfully combating two decades of deflation, monetary policy will remain loose given that inflation is shackled, and though P/E ratios are high, they are not yet stratospheric. There is some merit in all of these arguments. But as can be seen from the chart below, there is a growing gap between the financial markets and the real economy that cannot be ignored. It seems that "X" marks the spot where global investor rationality lost its way.

World GDP Consensus vs Equity Prices

Source: Zerohedge

The overall picture is one of growing risk and inadequate potential return in many markets around the world, yet investors seem alarmingly complacent. Given this backdrop, it appears likely that things will get worse before they get better.

USA: CAPE fear

Early 2014 has seen a spate of lacklustre statistics out of the US, from disappointing jobs data to weak manufacturing orders and car sales. The country has endured an unusually bitter winter, with punishing snowfall and record low temperatures. Optimists contend that this has disrupted economic activity and the underwhelming figures should therefore be taken with a truckload of salt. However, there’s more to the story than just bad weather. Car sales and housing indicators, for example, started to weaken before the snow set in.

Recent data does seem to show an improvement as encouraging jobs reports and elevated PMI data all helped to banish winter blues. But if the improvement is tepid then eventually the market will begin to question whether the US can sustain a period of rapid growth. Equity valuations would then come under pressure given the preponderance of optimism in the market.

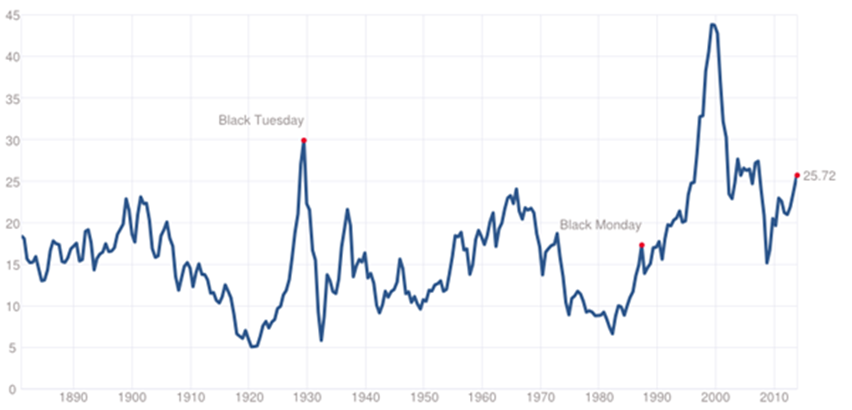

Valuations are certainly now

a problem in the US. Let’s take a long term valuation model like Nobel Prize

winner Robert Shiller's cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE).

Unlike the trailing 12-month P/E ratio, Shiller's CAPE smooths out earnings,

helping to avoid

potential false signals by

dividing the market's current price by the average inflation-adjusted earnings

over the past 10 years. This is particularly important in years such as 2013,

when corporate profits may be juiced up by consumers buoyed by rapidly

inflating asset prices, which are likely to prove transient. Except for relatively brief

windows prior to the crashes in 1929, 2000 and 2007,

Shiller's CAPE ratio has never been as expensive as it is today.

Shiller's CAPE ratio

Source: Multpl

Of course, the market can stay at this elevated level long enough to make investors even more complacent, as it did prior to 2007. After all, nothing sedates rationality like large doses of effortless money. But with valuations so high, there is little margin for error. Anything that causes earnings estimates on the S&P to be cut is clearly damaging.

Europe: The price is a blight

There is no doubt that the situation in Europe is better than it was. Business activity is at its highest level for 2½ years, many countries are now running balance of payments surpluses, and government debt is starting to fall for the first time in nearly six years. But again there are signs of complacency from investors, many of whom are starting to forget the Eurozone crisis, despite many of its root causes remaining unresolved.

For example, the European banking system continues to be seriously under-capitalised. The ECB has recognised this and will subject over 100 banks to an Asset Quality Review and stress tests later this year, likely exposing a tier one capital shortfall of at least €500 billion. This will squeeze lending activity across the Eurozone, a trend that is already underway. Indeed, most banks have seen the writing on the wall and are already preparing for higher capital standards by reining in lending, adding to considerable disinflationary pressures in the region.

Euro area loans to private sector

Source: ECB/WSJ

Also leading to stagnating prices is a lack of wage growth due to an unemployment rate stuck near record highs at 12%. European Central Bank president Mario Draghi has welcomed unit labour cost declines in Portugal, Greece and Spain. And in one sense he’s right as these adjustments do improve the region’s competitiveness. But if unit labour costs are falling because nominal wage growth is zero and productivity is positive, then inflation in those countries will by definition be negative.

The inflation trend is unequivocally downward (see chart below) and there is nothing to suggest that it is about to change. Europe seems to be entering a twilight zone of ultra-low inflation and is probably only one major shock away from outright deflation. In fact, stripping out the effects of one-off austerity driven tax hikes, 23 out of 28 countries including Italy, France, Spain and the Netherlands have been in outright deflation since mid-2013.

Euro area inflation rate

Source: Trading Economics/Eurostat

This is important because many nations still have onerous debt/GDP ratios well above 100%. If nominal interest rates are above nominal GDP growth in these countries, their ability to service debt becomes ever more compromised. One solution to the problem would be a weaker euro, allowing the region to gain competitiveness against the rest of the world and steal someone else’s lunch.

However, so long as an over-optimistic ECB runs an inappropriately tight monetary policy (its balance sheet is shrinking while the Fed and BoJ continue to expand theirs), the euro will likely appreciate. Consequently, there is still a real risk of another flare-up of the Eurozone debt crisis.

Japan: Noh drama, unfortunately

Waiting for an export recovery in Japan feels like a Noh drama, the country’s traditional theatre that can last all day. Given a 20% reduction in the yen, exports should have risen significantly in the last 2 years, but in volume terms they’re virtually unchanged.

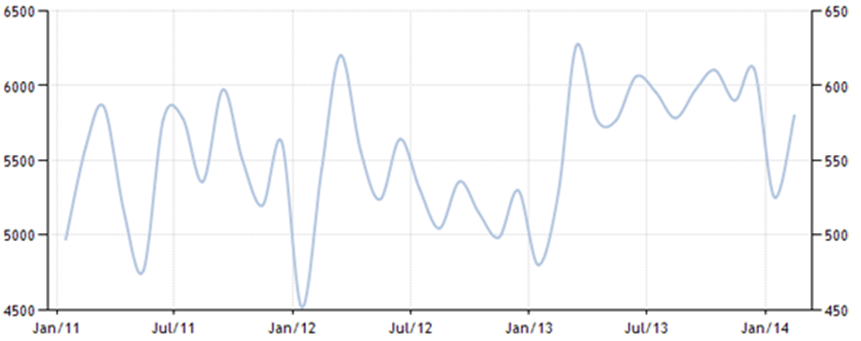

Japanese exports (JPY Billion)

Source: Trading Economics/Ministry of Finance Japan

The main reason for this is that companies have largely left their prices for goods sold abroad unchanged, preferring to pocket the effect of the weaker yen in super-normal profits. Indeed, Japan Inc doubled profits last year – its best performance since 2007 – but rather than selling more goods more profitably and stealing market share, much of these gains were simply a reflection of dollars and euros converting into more yen. In fact, the lower yen accounted for some 80% of the jump in manufacturers’ net profits. Of course, the trouble with such foreign exchange-fuelled profits is that they’re not sustainable. With far more muted depreciation likely this year, the advantage could quickly be erased.

Moreover, the weaker currency is now less advantageous in terms of a lower cost base because of the long-term trend in Japan towards localising production. For example, in 2005 more than half the cars Toyota produced were made at home. Now it is about 40%.

We’re also playing the waiting game in terms of wage rises. Though regular salaries finally rose last month after nearly two years of decline, the increase was a barely perceptible 0.1%, and overall pay actually declined 0.2%. Despite significant political pressure from Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, wages are still basically flat or down year-on-year. This means that real incomes are declining given that inflation has gone from -0.9% to +1.5%.

Limited gains in exports and wages will make it harder for Abe to steer the nation through the economic turbulence that’s likely after April’s consumption tax hike. Yet against this backdrop, the BoJ has maintained its upbeat forecast that inflation will reach 2% by the end of 2015. It would seem extremely difficult for the central bank to engage in a second round of monetary stimulus while maintaining such a prediction. However, if data in the real economy is sufficiently bad to warrant a revision to the forecast, this will provide leeway to stimulate further. Therefore the situation may need to get worse before it gets better.

Ultimately though, the government needs to adopt a structural approach to the country’s chief problem – too much income hoarded by businesses – in order to incentivise firms to part with their cash in ways that either boost labour income or productivity growth.

China: Bears in a China shop

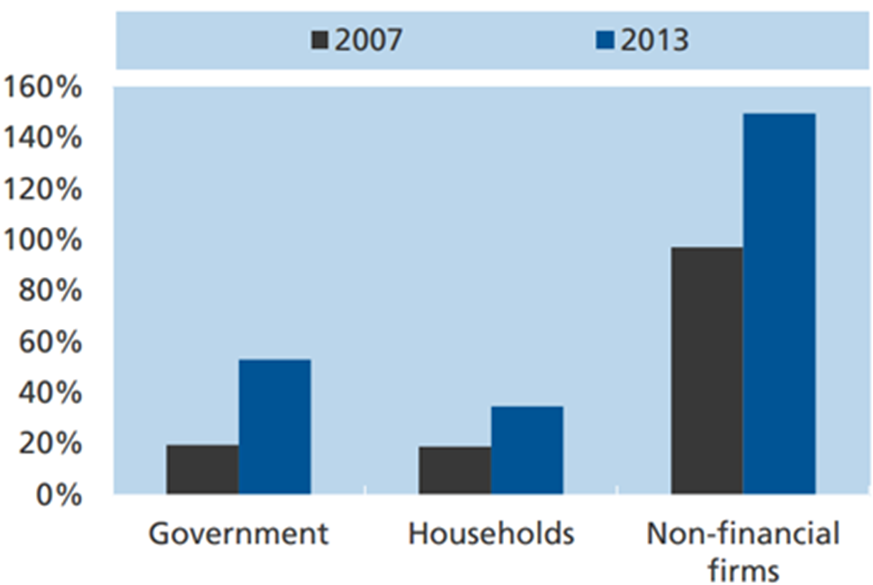

Such an event is now a

very real prospect given that China’s total debt as a proportion of GDP has

surged since the Great Financial Crisis (see chart below), leading to more and

more loans going to wasteful endeavours. Five years ago it took just over $1 of

debt to generate $1 of economic growth in the country. Last year it took nearly

$4 – and one-third of new borrowing now goes to pay off the old.

China’s non-financial debt as % of GDP

Source: Lombard Street Research

Policy makers are acutely aware that that they face a conundrum. Without structural reforms, the misallocation of resources will continue. Eventually there will be a crash. The longer the can is kicked down the road, the more certain that crash becomes and the bigger it will be. It’s possible to project costs so big that the regime itself could be threatened. On the flipside, structural reform will stunt near term growth. This also places pressure on the government, which needs to placate the masses and maintain social stability by generating enough GDP expansion to create up to 10m jobs a year. So far, the government has committed to equally ambitious growth targets and reforms. Something’s gotta give.

Sentiment towards China is decidedly bearish. But once the uncertainty over government policy has faded, the rock-bottom valuations should allow the bull case to shine through. Indeed, China remains a compelling structural growth story. Deep fundamentals in terms of education and the need to raise living standards are still very positive. Moreover, the trade account surplus is testament to the success of Chinese exports, which are still competitive despite rapid wage inflation in recent years.

Emerging Markets: Broken BRIICS?

Emerging markets (EM) have been buffeted by a perfect storm of capital outflows, weakening currencies and slowing growth since Fed taper talk first began in May 2013. Until this point, extraordinarily expansive monetary policy in the US had provided a surge of private capital flowing into EM economies, allowing them to fund their substantial external deficits. In fact, The World Bank estimates that over 60% of all capital inflows into EM countries from 2009 to 2013 can be either directly or indirectly attributed to quantitative easing in the US.

However, following the taper announcement, many developed market investors began bringing their money home after years of chasing yield in risky places. These hot money outflows are leading to currency weakness in many EMs, meaning essentials such as food and energy, which are often imported, quickly become more expensive. As inflation rises, currencies are devalued further, and the cycle of decline continues. The combination of stubbornly high inflation and a chronic current account deficit is corrosive to any economy, let alone EM economies that are often forced to borrow in other currencies than their own. This is an uncomfortable time for many EM central bankers, who are being forced to raise interest rates to defend their currencies at a time when their economies are already slowing.

So far this year, nominal policy rates have risen at their fastest pace since the EM crises of the late 1990s, led by hikes in Turkey and Russia of 4.5% and 1.5% respectively. Overall, the real policy rate in EM ex-China rose by 1% between April 2013 and January 2014. However, at 0.8%, it is still fairly low by historical standards and remains negative in Mexico, India, Indonesia and Malaysia. Thus, while EMs have made some progress in addressing their imbalances, the adjustments appear far from complete.

Moreover, while the real effective exchange rate for EM ex-China has depreciated by 8.2% since last summer, it is still trading 0.4 standard deviations above its 10-year average, suggesting potential for further currency weakness and an escalation of the crisis.

That said, most EMs are far less vulnerable than they were before the previous crisis in 1997. They have flexible exchange rates that can act as shock absorbers; their reserves are higher (a massive $7.7 trillion); their current-account deficits are smaller (the vast majority have a deficit under 5% of GDP); and their debts are lower and more likely to be denominated in domestic currency. The wild card is panic. Even if the economic fundamentals do not warrant a large-scale flight by investors, currency crises can become self-fulfilling, particularly in relatively illiquid markets.

But as John F Kennedy once said, “When written in Chinese, the word ‘crisis’ is composed of two characters. One represents danger and the other represents opportunity.” Once the imbalances have been corrected, either through increased competitiveness or lower domestic demand, it will be back to fundamentals. Ultimately these are very compelling, with many EMs continuing to benefit from a new wave of consumer activity.

(See EM Consumption – Riding the Second Wave for our thoughts on why this key theme is relevant for investors in a lower growth environment).

Also extremely compelling are valuations in the asset class. Indeed, on a three year basis, investors have never lost money investing at these levels and the average return is in excess of 100%.

Dark cloud, silver lining

There is a dark cloud of uncertainty enveloping global markets. Yet many bourses continue their seemingly inexorable rally and appetite for riskier assets grows stronger, underpinned by ongoing ultra-loose monetary policy. HSBC’s chief economist Stephen King skilfully sums up the current state of play, comparing central banks to a tiger in a zoo. The tiger appears to be behaving oddly, beckoning people over to its cage. One man strolls over, close enough to have a conversation – for this is a talking tiger – but, for good reason, not too close.

The tiger offers the man a proposition: “Come into my cage…there’s a huge pile of money in here, useless to me, of course, but maybe useful to you.” The man scratches his head, pondering. The tiger observes the man’s caution and offers reassurance. “Don’t worry,” he says, comfortingly. “I’m a different kind of tiger. I’m a vegetarian. You’ll be perfectly safe with me.” The man enters the cage and begins hastily pocketing the pile of notes.

Unfortunately, however, the tiger did like his meat after all.

Complacent investors are busy taking the money as their thirst for higher-yielding assets drives them into the riskier corners of equity and credit markets. Their fate may be much the same as the intrepid zoo-goer.

Consequently, we will remain very light on risk, with a strong commitment to preserve capital until a tradeable theme becomes apparent. Such themes should emerge over the coming quarters as the clouds of uncertainty slowly evaporate, revealing lucrative investment opportunities.

Extending the analogy, what may be needed in some countries is a clearing event, like a debt crisis in China, to truly kick-start the next bull market. Just as monsoon rains cool an overheating tropical landscape, such an event could clear the air, wash away toxic pollution and refresh global markets. Dark cloud, silver lining.

Nothing in this document constitutes or should be treated as investment advice or an offer to buy or sell any security or other investment. TT is authorised and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).