In this issue of our ‘Thoughts from the Ideas Factory’ white paper series, Rob James and our Global Emerging Markets (“GEM”) team examine how consumption patterns are changing in Emerging Markets and the opportunities this is providing for investors as we look forward over the next decade and beyond.

1. Introduction

In the 1990s, planning a journey to investment meetings across most EM cities was a lottery. Generally it involved navigating half constructed roads, fighting a throng of pedestrians and bicycles meandering down the streets. The occasional waft of smoke would emerge from the many street vendors selling local delicacies with the odd domestic pet attempting a dash for freedom through the moving traffic. For the consumer back then, advertising bill boards littered the sky line, promoting the political party of the day, the next soap opera to appear on the communal TV (often the same thing), or the social benefits of consuming a local brand of beer.

Today, most EM capitals resemble western cities. Traffic congestion has not changed much, but motorcycles and cars have replaced bicycles. Pedestrians are more likely to be congregating in the local supermarket and the advertising hoardings will carry the same brands and products as we see on the streets of London. The great opportunities of the past for EM investors lay in this visible transition to urbanisation and rising real incomes. The broadening of the middle classes fuelled demand for consumer products ranging from cars to mobile phones, processed foods to branded beers, televisions to washing machines. This is now changing.

As the penetration and prevalence of such products increases and even begins to plateau, so the number of ‘first time buyers’ of such products begins to slow.

We can see examples of this across EM: the percentage of rural Chinese who have a refrigerator has increased 5-fold since the turn of the millennium to 62% now, while 97% of urban Chinese already own both a fridge and a washing machine; Mexico, Argentina and Chile have become the highest consumers of soft drinks by volume in the world; mobile phone penetration is above 100% in a host of EMs from South Africa and Turkey to Thailand and Colombia.

That is not to say that there aren’t some outstanding structural growth stories still intact – Indian food retail for example is still a very fragmented market with thousands of small and traditional retail outlets accounting for over 95% of sales.

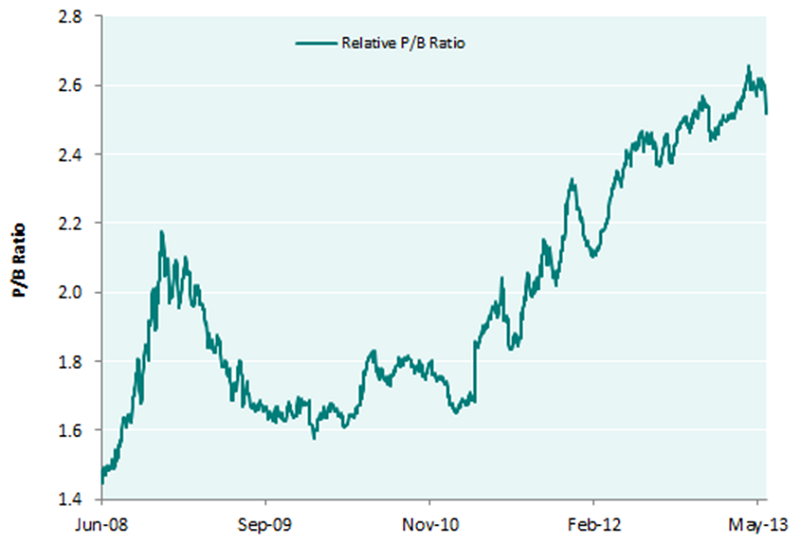

We’ve witnessed two trends related to this. First, set within the broader context of anaemic global growth, the pockets of emerging markets which still offer stellar growth rates in demand for consumer goods have seen a strong re-rating of the multiple they trade on, as have those stocks within the market that provide the best exposure to this.

Chart 1: MSCI EM Consumer Staples vs MSCI EM relative P/B ratio

Source: TT International | Bloomberg | MSCI

Second, investors are increasingly risk tolerant when in search of equities with exposure to less penetrated consumer markets. The performance of Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Kenya and other off-benchmark or frontier markets is evidence of growing willingness by investors to accept heightened currency, governance and liquidity risk in search of the first stages of emerging consumer. While we also actively seek out and invest in attractive companies in frontier markets, we remain aware of the risks of these markets and sensitive to the premium investors must pay to share in their growth.

2. Growing Sophistication

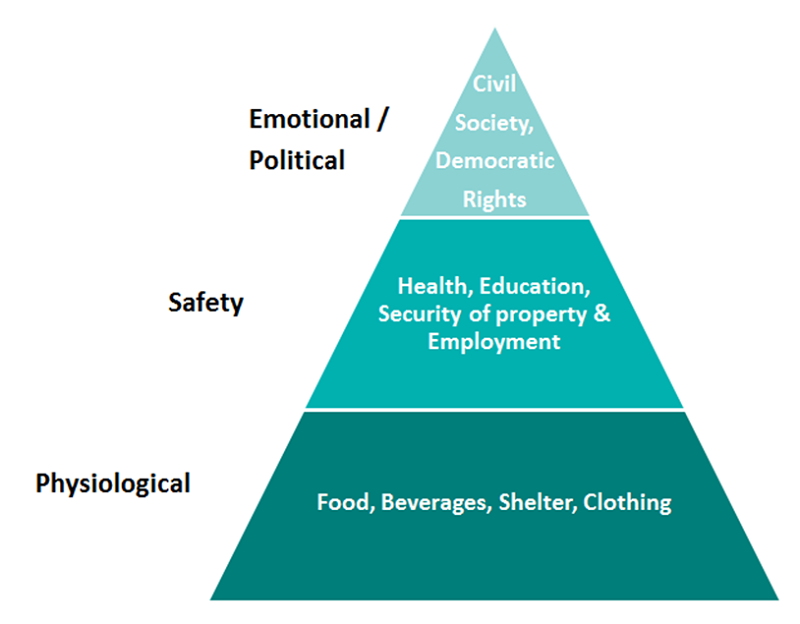

Yet the rise of the emerging consumer goes well beyond simply what people will eat, drink and wear, beyond what vehicle they will drive and where they will live. Psychologist Abraham Maslow posited the following hierarchy of human needs:

Chart 2: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Source: TT International | DataStream | MSCI

Much of the emerging consumer story thus far has been about the necessities – those physiological needs at the base of the Maslow pyramid. As the wealth of the emerging middle classes has grown, so too have their aspirations. Health, education and financial security become more pressing needs and it’s in these areas that we see a fresh leg of emerging consumption gathering momentum.

In healthcare

we see the rise of private hospital groups, diagnostics companies and health

insurers – partly reacting to deficiencies in the care offered by the state and

partly prompted by the spread of Western ‘lifestyle diseases’ in countries

where previously they were not prevalent. In the education space there are

growing numbers of listed education providers catering for primary to

post-graduate education. Supporting them are long distance learning innovators

and suppliers of materials. The increasing penetration and sophistication of financial

products in emerging markets is driving the growth of insurers,

brokers, and asset managers, but also Real Estate Investment Trust (“REITs”),

as pension managers seek alternative and longer duration asset classes in which

to invest their clients’ money. These three sectors have perhaps been

overlooked due to the lack of tangible or visible products associated with

them, or because until now there has been a relative paucity of ways to invest

in them. Yet they represent a strong corollary of the consumption boom that

GEMs have enjoyed – The Second Wave of Growth.

3. Role of the State

Rising wealth and expanding aspirations explain the origins of the demand side of the second consumer wave we have identified but there’s also a story to be told on the supply side. The Great Financial Crisis and its aftermath have brutally laid bare the limitations of the welfare state in mature capitalist democracies and prompted a global rethinking about the role of the state - what it can achieve and what it ought to try to achieve. While developed economies increasingly either rely on private provision of these social goods or, as in the UK, look to the broader ‘Big Society’ to take the role of the beleaguered state, emerging economies are in the fortunate position of being at early stages in developing the architecture of their welfare states.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs also serves as a useful guide for non-democratic EM governments to consider what they must do to avoid being overthrown. Previously it was enough to provide modern homes and white goods to those who never had owned them. The new generation have more demands: they want their children to go to good schools, they want to get a decent return on their savings and they want quality healthcare when they become ill.

Forward-thinking emerging markets are responding with new economic models that create ‘enabling environments,’ incentivising the private sector and the individual to take responsibility rather than over-burden the state. In turn this creates opportunities for listed companies to meet these growing needs and generate handsome profits for those who invest in them.

Let’s consider each of the service sectors we’ve identified in turn, taking a closer look at the investment opportunities that are presented.

4. Health Care

Health systems in the emerging world suffer from inadequate resources. E.g. there are 3.5 doctors per 1000 people in Germany and 2.8 in the UK, compared to 1.9 in the UAE, 1.5 in Turkey, 0.8 in South Africa and just 0.2 in Indonesia. Second, they also are suffering from rapid growth in ‘lifestyle’ diseases as Western consumer habits spread – six countries in MENA are in the global top 10 for diabetes, and China’s 40% death rate due to cardiovascular diseases is amongst the highest in the world. Third, emerging markets are starting to suffer from demographic indigestion as booming populations start to age. E.g. the number of over-60s in India is expected to increase from 100m presently to over 300m by 2050; Chinese over 65s are to increase by 200% to 330m by the same point.

Investment opportunities arising from this have predominantly centred around private hospital groups – many of which have floated on stock markets over the last couple of years. Typically these companies have generated robust top line growth driven by the combination of growing number of beds, higher numbers of patient visits, greater length of stay due to disease burden, and price increases. Given high levels of fixed costs this revenue growth has seen these companies expand their margins as costs are diluted. Private health providers are often seen in an antagonistic or competitive relationship to the state system in developed economies but many EMs are making efforts to facilitate the private sector.

South Africa is one such example where the state has provided such an environment and the private sector has responded. In March 2012 the government changed the tax benefit on private medical schemes to positively favour low income people by introducing tax credits. The health insurance sector has responded too, developing products for low income earners. A similar attempt by the state to create the right ‘enabling environment’ for the flourishing of private provision has been seen in the UAE. Abu Dhabi, having previously provided free healthcare to all residents, has switched to a system of requiring everyone to have private medical insurance whilst still paying forindigenous Emiratis. The success of this system, which has resulted in affordable coverage for both blue and white collar workers, is expected to becopied in Sharjah and Dubai, both of which recently introduced a draft bill for a similar mandatory private insurance scheme. Private health expenditure is already greater than 50% of the total in Brazil, India and the Philippines and the trend towards private over public provision seems inexorable.

5. Education

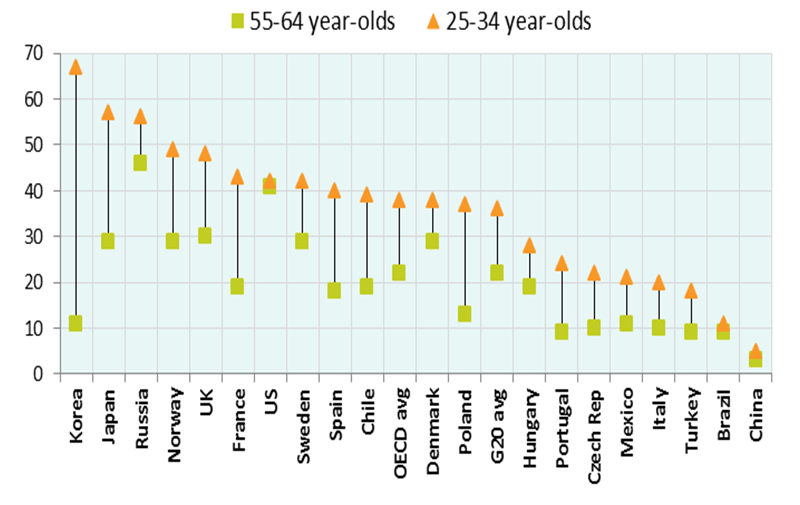

Chart 3: Percentage of population holding a post-secondary degree

Source: Education at a Glance 2012 : OECD Indicators

In pre-university education the government is helping to combat poor teacher quality and lack of resources by inviting private companies to develop ‘learning systems’ – integrated packages of materials, methods and instruction for teachers – to ensure the curriculum is delivered as effectively as possible.

The response from the Brazilian private sector has been remarkable to the extent that tertiary education provider Kroton, once their merger with rival Anhanguera has been completed, will be the largest listed education name in the world with over 1 million students. Private universities now educate 5 million of Brazil’s 7 million post-secondary students and private schools now account for 16% of Brazilian school children, from 12% in 2000. India stands out as another example of a country focused on harnessing the power of non-governmental actors in education. Already the share of university enrolment from private institutions has reached 59% in 2012, up from 33% in 2001. India’s 12th 5 year plan seeks to build on this through several key changes: (i) extending student financial aid to accredited private institutions (ii) providing access to research funding on an equal footing for private universities and (iii) re-examining of proposals to allow profit motive in private universities.

6. Financial Services

The growth in household assets and the desire to protect and further grow these assets, combined with the demographic impact of more people passing into old age, explains the increased need and demand for sophisticated financial products in emerging markets. This requirement has had a double impact – both on the financial products offered and on the development of asset classes necessary to meet new demands.

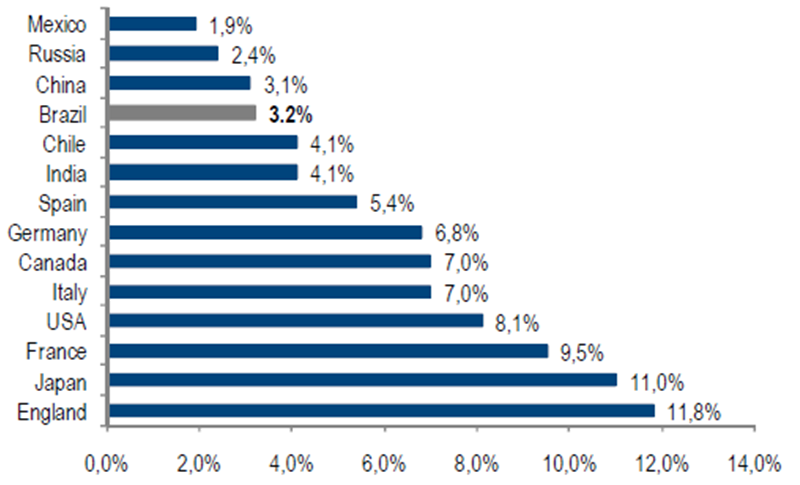

We’ve seen strong growth in asset management and insurance industries in these countries as rising real incomes allow people for the first time to start paying into a pension fund, buying mutual fund products or participating in various insurance schemes. The recent IPO of Banco do Brasil’s insurance vehicle, BB Seguridade, highlighted the strong growth the sector is showing – premium growth has enjoyed a CAGR of 17.2% from 2008 -2012 but penetration of insurance ex-healthcare remains at just 3.2% of GDP as shown in chart 4.Chart 4: Brazil’s penetration ratio* is lower than its peers

Source: Swiss Re and SUSEP *(insurance premiums as % of GDP). Data from 2011, ex-healthcare plans

7. Conclusion

Consumer demand in EM is shifting as people move up Maslow’s hierarchy and their needs and aspirations evolve. The old emerging consumption stories of staples and durables, while by no means fully played out, are being replaced by a new focus on consumption of services – especially health, education and sophisticated financial services. Not only is the demand-side evolving, but the way emerging markets supply these services is changing too. The Great Financial Crisis revealed the inherent fragility of the welfare state in its current form in many developed countries. EMs are generally embracing a model in which the state acts as a facilitator to unleash the power of private capital.

In turn this is creating opportunities for companies across a range of sectors. As the share of consumer demand becomes increasingly tilted towards these services, and the number of listed companies in these sectors grows, the challenge for the investor in emerging markets will be how to profit best from the “second wave” in emerging consumption. While many of these trends are in their first stages, understanding their drivers and consequences will help emerging market asset managers meet the challenge.

Nothing in this document constitutes or should be treated as investment advice or an offer to buy or sell any security or other investment. TT is authorised and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).