Corporate debt could be the culprit

Uncertainty is on the rise. That much is clear in increasing market volatility. Over the four trading days between 21st December and 27th December, the US flagship S&P 500 index went broadly nowhere in aggregate, yet in the process fell 6% in two days, before recouping its losses entirely over the next two days.

Such volatility is perhaps unsurprising. The protracted recovery enjoyed by economies and markets over the past decade has been driven by exceptionally easy monetary policy and, in particular, Quantitative Easing. But the US is now well into its rate hiking cycle, and Quantitative Tightening is the order of the day. The European Central Bank, whilst some way off raising official rates, has also stepped back from Quantitative Easing. Put simply, the global liquidity tap has been turned off and the plug is slowly being pulled out. The previous environment of exceptionally low interest rates and aggressive central bank balance sheet expansion is unprecedented in economic history. Reversing this situation could lead to dangerous, unintended consequences. As a result, investors are beginning to question whether another crisis could be on the horizon and what might be the catalyst.

In addition to deteriorating global liquidity, investors also see several geopolitical flashpoints as potential causes of the next crisis. The unpredictability of President Trump and the rise of nationalism are certainly alarming. At the time of writing, US and Chinese trade negotiators are locked in talks. It is unclear at this stage whether tariffs are just sabre rattling by the Trump regime, designed to remind the world of the importance of the US and improve the country’s trading terms, or whether they will escalate further into full-blown protectionism. Of course, Trump is far from the only ‘strong man’ leader that is a major threat to the era of cooperation and globalisation. Presidents Putin, Duterte, and Bolsonaro spring to mind. With his unassailable power, China’s President Xi could also come under this label.

Europe is not without issues either. Brexit dominates the news in the UK, with no clear path ahead and the deadline for exit looming large. In France, President Macron is wrestling with widespread anger and protest, and far from rising to become the new de facto leader of Europe, has seen his popularity plummet. Merkel has also lost her crown, and is fast becoming politically impotent, while Italy is experimenting with populist expansive policies, despite a weakening economy. The European Union itself has elections in May. These are likely to herald a significant transfer of power from the centrist coalitions to extreme parties on both the left and right, with important implications for the future direction of the bloc.

All these issues have the potential to precipitate a crisis. However, to quote Donald Rumsfeld, the former US Secretary of Defence, these are all ‘known unknowns.’ It is in fact a lesser-known unknown that gives us the greatest cause for concern – dislocation within credit markets. That there is risk in the high yield bond market should not surprise readers, and it is thus the investment grade market in which a deterioration would be more likely to cause an unexpected financial shock. It is here where we believe that there is more vulnerability than is generally perceived, both in terms of credit risk and interest rate risk.

Bigger isn’t always better

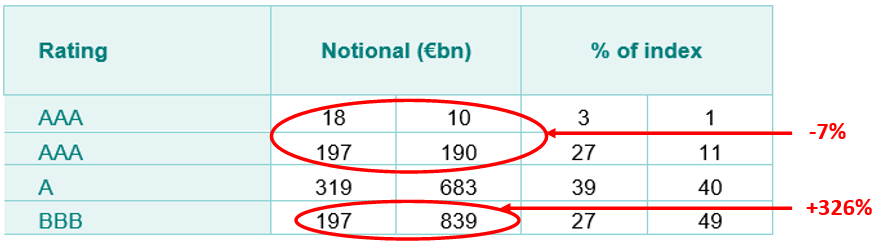

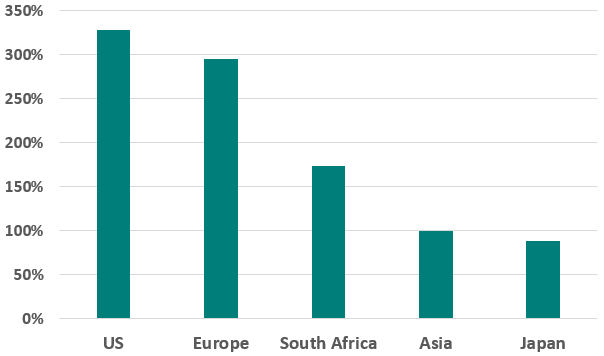

The investment grade corporate bond market has swelled in recent years as a prolonged period of low interest rates has made it tempting to take on more debt. However, not all segments of the market have expanded. Indeed, in Europe the notional value of the highest quality bonds – those rated AAA and AA – has declined by 7% over the last decade, while the value of the lowest investment grade debt – BBB – has grown over 300%. This suggests that credit quality in the European investment grade market has deteriorated markedly.

Corporate bond rating comparison 2007 vs 2017

Source: Citi Research

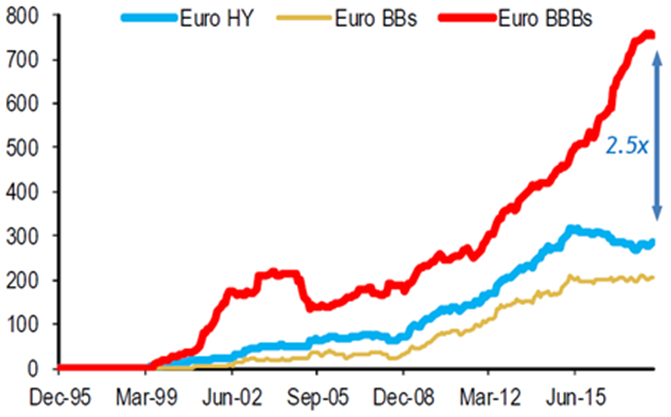

It is a similar story in the US, where the value of investment grade debt has ballooned from $2 trillion in 2007 to $6 trillion today. This is approximately one-third of US GDP. Again, this rise has been driven predominately by growth in lower quality BBB debt, which has expanded from $750bn to $3 trillion over the same period. Importantly, the BBB market is now more than twice the size of the high yield market in both Europe and the US.

Size of market (Eur Bn face value)

Source: BoAML

This creates a capacity problem and means that any material downgrades from BBB to high yield would swamp the high yield market, making them difficult to absorb. Unfortunately, such sweeping downgrades may be imminent. Indeed, in the US, over $220bn of investment grade debt is already in cross-over territory or on review for downgrade at mid-BBB or low-BBB with at least one ratings agency. That is more than 20% of the outstanding high yield market.

So what could be the catalyst for major downgrades?

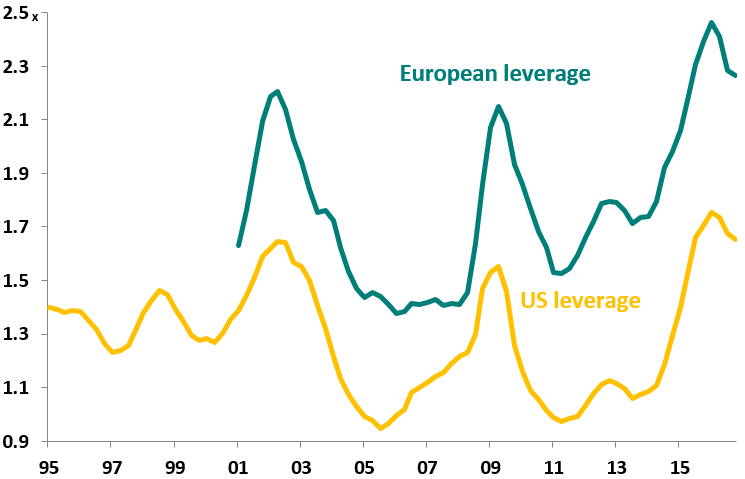

As

mentioned above, companies have taken on significantly more debt as interest

rates have fallen. They have also sought to make their balance sheets more

“efficient” by raising debt and taking advantage of the tax deductibility of

interest payments. This behaviour has been encouraged by investors,

particularly in the US, pressing for more share buy backs in to order to

maintain attractive EPS growth amid a slow growth global economy. Thus,

leverage has increased substantially.

Leverage (Net Debt/EBITDA)

Source: Citi Research, Bloomberg

For BBB debt, the figures are even more stark. In 2000, the net leverage ratio for BBB issuers was 1.7. It is now 2.9.

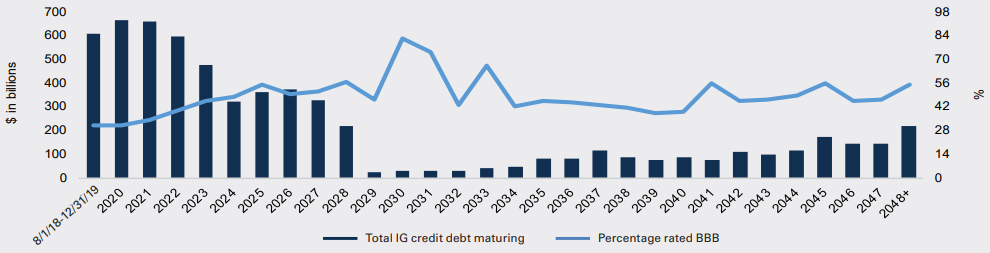

Such an increase in the overall amount of corporate debt means that relatively small rises in interest rates can significantly increase the cost of servicing debt. This problem will be exacerbated as fixed term debt matures and is refinanced at higher rates. Between now and 2022, some $2.5 trillion of US investment grade corporate debt will mature – almost half the entire market.

Maturity schedule for investment grade debt

Source: Tortoise Advisors. Bloomberg-Barclays Short Term Corporate Index (all data inside one year); Bloomberg-Barclays US Corporate Investment Grade Index. As of 8/1/2018.

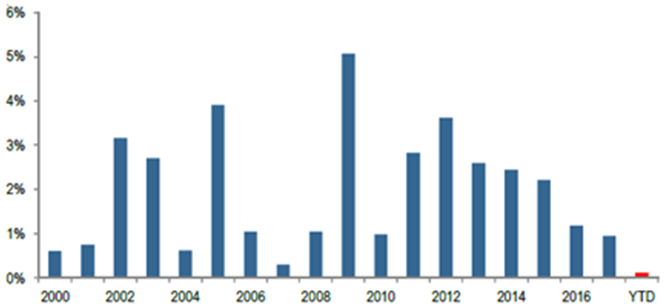

In addition to the risks associated with refinancing debt in a rising rate environment, companies may face slowing sales and falling margins as the economic slowdown intensifies. There is plenty of evidence that this is already underway. US PMIs have fallen, the Chinese manufacturing sector is in contractionary territory for the first time in two years, and some of Europe’s largest economies are now on the brink of recession. To get a sense of how a recession could impact the corporate bond market, it is useful to look at the rate of Fallen Angels – investment grade bonds that have been downgraded to high yield. This averaged just 1.9% in Europe during recent benign years. However, in a period of market dislocation and recession such as 2009, this could potentially rise to 5%.

Fallen Angel rate

Source: JP Morgan, Markit Group. Data to Oct 2018.

Put another way, approximately €100-120bn of European bonds could be cut from investment grade to high yield during the next recession. Whilst not our central expectation, it is not inconceivable that the US economy could also see recessionary conditions in 2019 or 2020. Protectionism or a policy error by the Fed are both potential catalysts for this. As the economic cycle matures, so companies may find themselves facing a perfect storm of slowing sales, falling margins, and rising interest costs.

If a sweeping credit downgrade does occur, the fallout is likely to be exacerbated by forced selling. Indeed, in the search for yield, there has been an explosion in investment grade bond funds, bought by institutional and retail investors alike. Unsurprisingly, many of these funds cannot own debt that is not investment grade. Consequently, they would be forced to sell their positions, amplifying the losses. They would likely be joined in the rush for the exit by retail investors, who often sell en masse during periods of sharp price weakness. The problem could be compounded further by declining liquidity in the corporate bond market as big banks have withdrawn from the market-making business due to regulatory changes. This has seen them cut their trading inventories of corporate bonds by around 80% over the last decade, meaning their ability to absorb such widespread selling would be dramatically reduced.

Major corporate debt downgrades and wider credit spreads will cause problems for heavily indebted companies with overstretched balanced sheets, banks, and life insurers with significant exposure to the US and Europe. As sovereign bond yields fell to exceptionally low levels in recent years, life insurers increasingly moved their holdings into corporate bonds. Unfortunately, these are now a vast proportion of their net asset values.

Global life insurers – corporate bonds as % of NAV (2017)

Source: Company reports and JP Morgan

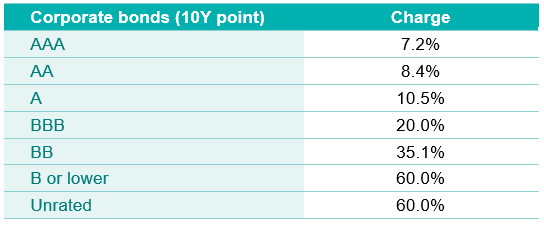

If bond ratings decline, the capital required for life insurers to hold such bonds rises sharply. For example, as the table below shows, a downgrade from BBB to BB causes the capital requirement to increase from 20% to over 35%.

Bond ratings vs life insurer capital charges

Source: JP Morgan

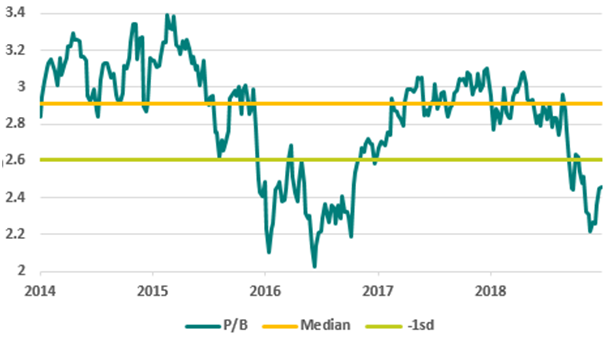

Although life insurer solvency ratios are generally strong, this is partly because credit spreads are tight. Of course, credit spreads have been kept artificially low by ultra-accommodative monetary policy. As central banks withdraw such support, spreads will widen. Without volatility adjustments and other smoothing benefits, life insurers in Europe would on average lose 30 percentage points of solvency for every 100bps increase in credit spreads. Thus, if a deterioration in the credit market weakens life insurer solvency ratios and dividend cover, they could come under pressure. That said, we do think this issue will largely be confined to Europe and the US. Life insurers with substantial exposure to Asia continue to have many positive attributes. We believe they are well positioned to take advantage of strong structural growth opportunities, have less exposure to corporate debt, and trade at extremely attractive valuations. For example, Prudential is currently 1.5 standard deviations cheap on a price/book basis over a 5-year period. Put another way, even if one ascribes zero value to Jackson, Prudential’s US business, then the implied valuation of the fast-growing Asian business is just 1.07x EV – significantly cheaper than close comparable AIA Group.

Prudential price/book ratio

Source: TT International, Bloomberg

Such attractive valuations are likely to mitigate short-term downside risk in the event of a credit downgrade, and do not seem to accurately reflect the company’s exciting longer-term growth opportunities in Asia. However, life insurers with less compelling valuations and more exposure to Europe and the US could be tested. Banks would also be impacted, but to a lesser extent as their bond holdings are heavily skewed towards sovereign debt, given the higher liquidity requirements imposed on banks following the Global Financial Crisis.

Financial crises tend to involve at least one of these three key ingredients: excessive borrowing, concentrated positions and a mismatch between assets and liabilities. The Global Financial Crisis was so damaging because it involved all three – huge bets on structured products linked to the housing market, and bank balance sheets that were overstretched and heavily reliant on short-term funding. The corporate bond market already contains two of these toxic ingredients. Companies have become steadily more levered over the past decade, and corporate bond holdings are increasingly concentrated in lower quality issuers. This situation has been manageable during the recent benign period, but as companies come to refinance at a time of rising rates and falling profits, the corporate bond market could prove to be the fault line of the next crisis.