After a recent research visit, EM Portfolio Manager Rob James discusses the opportunities and challenges facing Pakistan.

Albert Einstein once said: “Information is not knowledge. The only source of knowledge is experience”. With this in mind, I embarked on a research visit to Pakistan to get a first-hand account of the opportunities and challenges facing the world’s sixth-most populous country. I did not leave disappointed, having gleaned important insights from executives, academics, central bankers and finance ministers. This WorldWatch summarises my main conclusions.

The trip felt like a journey across two countries, from the chaos of Karachi to the serenity of Lahore and Islamabad. It provided a glimpse into the challenges of developing a nation divided into several distinct provinces, each with loose tribal affiliations and governance structures of varying economic competence.

Pakistan’s governance as a whole has been so poor that military interjections into politics are the norm, rather than the exception. The massacre of 132 Peshawar school children in late 2014 marked a watershed moment; an event so traumatic that it had the power to unite leaders across the military and political spectra. The army has since begun a successful campaign to tighten up on security, leaving a democratically elected government to focus on the essential task of the administering the country. This has led to a newfound sense of stability and rising levels of confidence. Couple this with $46 billion of Chinese investment and technical know-how to develop the Power sector – the main bottleneck to growth – and the outlook for sustainable economic progress in Pakistan looks brighter than it has done for some time.

Reform progress

Pakistan has been making steady progress on reforms since late 2013, when it agreed to implement an IMF programme in exchange for a $6.6 billion loan. The IMF’s agenda is focused on the following key issues:

- Saving the windfall from falling oil prices to

strengthen foreign exchange reserves and insulate against external shocks

- Preventing a further loss of export

competitiveness

- Reducing electricity subsidies

- Broadening the tax base and improving tax

administration: merging the identity card system with the tax system should

allow 150 million people to be monitored

- Making progress on safeguarding financial

stability and expanding credit growth

- Unlocking Pakistan’s long-term growth potential

by making structural reforms in the Energy sector, addressing central bank

independence, developing an anti-money laundering framework, and improving

public debt management, trade, and the business climate

IMF programmes have had mixed success in Emerging Markets, but where there is a combination of political will and technical know-how, the improvements can be dramatic. For example, Latin American programmes in the 1980s and 1990s promoted fiscal adjustments and were undoubtedly responsible for catalysing important structural reforms, including Utilities sector privatisation and pension deregulation. One can only hope that Pakistan follows Chile’s lead and sticks to the programme rather than emulating the sporadic commitment shown by Brazil.

During my visit, I met with Dr Werner E Liepach, Country Director for the Asian Development Bank, who is tasked with prioritising a sister $4.4 billion programme to facilitate structural change. In a wide-ranging conversation, he was complimentary on Pakistan’s achievements to date, but realistic on the hurdles still to be overcome. On the one hand, the country has never got so far in an IMF programme, which has now completed its eighth review. On the other hand, widening the tax base, crowding in the private sector and tackling corruption are still required to enable Pakistan’s growth to rival the ASEAN tigers.

Fiscal challenges

Following the trauma of partition from India in 1947, Pakistan was assumed to have huge potential for growth, unencumbered by the caste system and blessed with fertile agricultural land and sophisticated irrigation on the Punjab. Fast forward 60 years and the country flounders at the bottom of the income per capital league tables, whilst lurching from one bailout to the next. To understand why, we must first understand the fiscal challenges facing Pakistan. The problem was elucidated by meetings with Dr Avesha Ghous, Finance Minister of Punjab, and Ejaz Wasti, Economic Adviser to the Government of Pakistan.

They informed me that 200,000 new tax payers will enter the system in 2015, taking the grand total to 700,000 people underwriting government spending. This is in a country of nearly 200 million citizens. Even taking into account the fact that 50-60% of the population is under the age of 24, 700,000 is a tiny number. Consequently, tax revenue as a percentage of GDP is about 8% in Pakistan, low even by Emerging Market standards. The government has a medium-term target to raise this to a respectable 15%.

Progress has undoubtedly been made in collecting taxes from Pakistan’s formal economy. For example, ministers have removed tax exemptions, unified VAT and increased taxes on luxury goods. Partly as a result of these measures, tax contributions have risen by 30% and Pakistan’s fiscal deficit is forecast to shrink to 3.8% of GDP next year, after peaking at 7.6% in 2008. Moreover, there is scope to collect more taxes from the country’s formal sectors. Take the Telecoms industry. 100 million Pakistanis have a mobile phone, yet only 20 million have a bank account. This represents a huge opportunity for banking penetration, and by extension tax collection. Such a convergence has already been achieved in Kenya, where Safaricom has 18 million customers on its money transfer facility, making it the largest bank operator in the country. Its mobile money payments are growing at a CAGR of 20%.

Ultimately however, for Pakistan’s economy to become self-sustaining, the government must develop a tax base for the country’s vast informal sectors. This will be extremely challenging. Indeed, targeting powerful voting blocs such as the rural sector, which represents upwards of 40% of the labour force, has been described as political suicide in the run up to next year’s election.

Source: USAID. Pakistan’s government must find a way to tax the country’s rural economy.

Crowding in

As the government looks to address its fiscal challenges by increasing tax revenue, it will also need to reduce spending. This gives the private sector a unique opportunity to fill the gap, with banks increasing their lending to businesses as opposed to simply using their deposit base to buy high yielding government bonds. Known as ‘crowding in’, this thesis was extoled by both the central bank and the Finance Ministry. It must be said that there was no transformative narrative echoed by the private sector banks, with the most optimistic of them predicting a 10% increase in consumer/SME loans next year. In our view, however, this is simply too low for an under-penetrated Emerging Market and will inevitably have to accelerate. This represents a meaningful upside surprise for economic activity. My suspicion is that the boost from higher private lending will kick in from 2017, when many of the 3-year government loans have matured and when megaprojects such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor are well under way.

Monetary policy

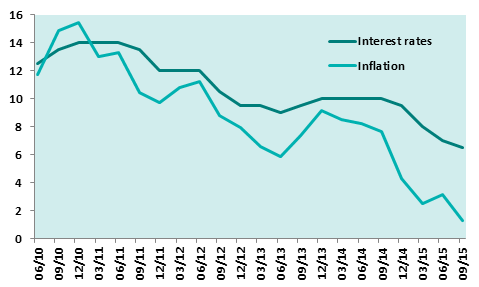

Of course, higher lending requires greater demand for loans, which itself needs subdued interest rates. Thankfully, monetary policy in Pakistan is extremely accommodative. Looking at the chart below it is easy to see why – inflation has simply collapsed.

Pakistani interest rates versus inflation (%)

Source: TT International, Bloomberg

This is partly explained by the falling oil price. Pakistan is a net oil importer, with oil imports accounting for about 5% of GDP in 2014. The windfall from cheaper oil has not only improved the current account, but also allowed the government to reduce energy subsidies to 0.7% of GDP. As the price of oil has fallen, so food has become cheaper due to bumper crop yields. The central bank described this as the ‘honeymoon period’ for inflation. By their projections, both inflation and interest rates will begin to pick up in 2016.

Privatisations

A great mentor once said to me “judge an Emerging Market's appetite for capitalism by looking at its national airline. Is it a flag bearer for the government, or a company like any other, open to market forces?” On this criterion, Pakistan International Airways (renamed Panic In Air by most of the locals!) remains under state control and is perhaps a negative litmus test for the country’s privatisation ambitions. But this may be about to change as PIA is now expected to be privatised in mid-2016.

Source: Wikimedia

It is certainly an interesting proposition. Under a new CEO, the airline is considering a revamp of its strategy to become an ‘ethnic carrier’, and recently fired 308 employees as part of an effort to remove individuals with fake qualifications (one was even rumoured to have been a pilot). PIA also has a ready source of cash in the form of its adventure in luxury hotels. The airline owns the 1000-room Roosevelt hotel, close to Grand Central Station in Manhattan, and the Scribe in Paris. Selling them could raise close to £1 billion, enough to wipe out decades of loans that cost £6 million every month in interest alone. However, because of the company’s history it remains susceptible to political interference. I read with interest that Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif recently spent a day with PIA’s management testing out the new business class seats. The company had scrapped these seats in a strategy to focus on economy, a decision that was derided as a national disgrace.

Aside from Pakistan’s national airline, there are many other interesting privatisation candidates, including several names in the Electricity sector, as well as Pakistan Steel Mills and Pakistan Railways. The IMF and Asian Development Bank have a modest target of offering or marketing at least one privatisation every quarter over the coming year. But even this relatively undemanding timetable looks optimistic as any privatisation efforts are likely to face stiff opposition. Imran Khan, the former cricketer and leader of a populist political party, has promised to fight any privatisation attempts with mass demonstrations. The criticism is that Prime Minister Sharif is intent on forcing through reforms without paying due attention to parliament or the constitution. Another criticism levelled at the government is that it has largely privatised dividend paying, ‘contributing’ companies rather than the many loss-making entities that it needs to get off its books.

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

Arguably the most popular talking point of the trip was the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a $46 billion package of investments in power and transport infrastructure that aims to connect China to Pakistan and the Gulf. Unlike China’s expansion into Africa, mostly to access raw materials, this programme is all about trade. It will save 800 nautical miles for Chinese businesses transporting their goods to new ports in southern Pakistan.

From Pakistan’s perspective, one of the most important aspects of the project will be the construction of new coal-fired power plants and hydroelectric dams. The plans envisage doubling Pakistan’s current electricity output, which will help to remove one of the key bottlenecks to growth. Indeed, the energy-starved country is beset by hours of daily scheduled power cuts because of a lack of supply, shutting down industry and making life miserable in homes.

Source: Wikimedia. Dams totaling 2,910 megawatts are to be built as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Another of Pakistan’s key problems – security – is also improving as a result of CPEC: the latest Karachi crime figures are down 70%. This is helping to facilitate a boom in construction and investment. As a result of these benefits, Pakistan’s central bank estimates that CPEC could add an incremental 1% to GDP growth per annum over the next 5 years.

Of course, our job is to assess how such developments can be turned into successful investments. We are therefore extremely interested in the impact that CPEC could have on Pakistan’s listed Cement sector. The CFO of Maple Leaf Cement put it quite succinctly, saying ‘the total cement being sold in Pakistan today is 26 million tons, with the rest being exported. The value of this domestic capacity in dollar terms is about $1.8 billion. If just $5 billion is allocated from CPEC per year and only 10% of this goes to the Cement industry, this will add $500 million of demand – simply mind boggling’.

However, what is also mind boggling is the potential for waste and inefficiencies within this kind of investment programme. The Asian Development Bank looked at one of the principal highways to China, studied traffic flow and made reasonable economic projections. They concluded that a four lane highway made sense from an economic perspective. The President immediately dismissed these economic arguments, saying it was important to have a six lane road. The ADB also pointed out that if previous planning is anything to go by, then new roads and stations will likely be constructed without considering the commercial potential of such infrastructure. It is here that there are lost opportunities. A further example of profligacy relates to the Metro bus line. The government wants to see raised terminals and flyovers dedicated to these buses, using Islamabad as the blueprint. Experiences around the world suggest that this model makes absolutely no economic sense, unless train terminals use the same infrastructure. Actually the real motivation for this largesse appears to be placating the contractors, who are busily 'smoothing' the land acquisition process for the government along the way.

Corporate potential

Such shady dealings demonstrate that corruption and corporate governance issues remain key challenges when seeking to invest in Pakistan. In the meetings I had with individual companies, nobody was prepared to call the Cement sector a cartel, but it is no coincidence that the ‘Cement Association’ conducts regular meetings to discuss the state of the industry (read coordinate pricing and capacity). In many ways this strong and disciplined pricing backdrop is part of the sector’s attraction. But questionable corporate governance can also lead to damaging business decisions such as DG Khan Cement’s recent move into the dairy business, when it spent $25 million of shareholders’ money to buy 5,000 cows. Obviously this diversification is not a ‘natural’ progression for a cement company.

However, if we keep a critical eye on corporate governance issues then there are some fantastic investment opportunities in Pakistan. From fridges to fertilisers and butter to bank loans, companies across all sectors highlighted the astonishing latent growth potential, almost irrespective of the prevailing macro backdrop. Such potential is enhanced by Pakistan’s key competitive advantage of low wages. Indeed, the average monthly wage in Pakistan is 1/3 of that in China at $280 versus $760. With CPEC now underway, many Chinese manufacturers could move their factories to take advantage of these lower wages.

Though Pakistan still faces many great challenges, it is undoubtedly becoming a land of opportunity. We recently took the important decision to invest in Pakistan in our GEM strategy through the purchase of Lucky Cement, the country’s largest cement producer.

Nothing in this document constitutes or should be treated as investment advice or an offer to buy or sell any security or other investment. TT is authorised and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).