Oil prices and the dollar are stronger, US Treasury yields are rising, and several EM currencies have seen sharp sell-offs. Many investors are worried that these are warning signs of further distress to come across Emerging Markets. To assess these risks, we have spent the last two weeks travelling to some of the world’s biggest economic trouble spots. The trip has helped to reinforce our view that some countries undoubtedly face further volatility, but widespread systemic weakness across Emerging Markets is unlikely.

As we enter a period of tightening global liquidity, investors are becoming concerned about potential vulnerability and contagion in Emerging Markets. In an effort to assess these risks, we have spent the last two weeks on the road, travelling to some of the world’s biggest economic trouble spots. Our meetings included an opportune presentation from Janet Yellen, as well as on the ground discussions with central bankers, political scientists, investors and corporates across Argentina, Brazil and Turkey. Our findings suggest further challenges ahead, but deep value beginning to emerge, with tentative signs of potential positive catalysts. The trip has helped to reinforce our view that some countries undoubtedly face further volatility, but widespread systemic weakness across Emerging Markets is unlikely.

It could be argued that history doesn’t give us much cause for comfort. Fed tightening in 1994 led to the Mexican peso crisis. A US rate hike in 1997 triggered the Asian crisis that swept through to Russia and Brazil before culminating in the debt default of Argentina in 2002. It was only the tightening cycle between 2004 and 2006 where the victim was not to be found in the emerging world. In fact, the subsequent deterioration in the US housing market led to a crisis of global proportions, allowing ‘emerging’ China to come of age and dig the world economy out of its slump.

Crucially however, we expect to avoid systemic Emerging Market weakness because we believe that the Fed will continue to tighten monetary policy gradually, and also because Emerging Markets are fundamentally different today compared to previous crises. Following our trip, we will continue to give Argentina the benefit of the doubt versus Turkey, given President Macri’s commitment to reform and several other potential positive near-term catalysts. While the political situation has become more challenging, the structural long-term opportunities in Argentina remain as compelling today as they were when we entered the market three years ago.

Today’s global tightening cycle is unique. It is the first time we have had to contend with rising interest rates alongside the unwinding of quantitative easing (QE). However, we were encouraged by a presentation from Janet Yellen and her interpretation of the priorities for current Fed governor, Jay Powell. Based on this discussion, we view the odds of Fed policy overkill as low. ‘Gradual’ was Yellen’s watchword.

The real Fed Funds rate, defined as the effective Fed Funds rate minus the median inflation rate, is still below zero. Powell will feel quite comfortable maintaining this position of being ‘behind the curve’. Indeed, the central bank has a desire to avoid inflation expectations being too well anchored at 2%, the danger being that the market views this 2% as a ‘ceiling’ for inflation, rather than a target. The difference is subtle but important as it implies that an overshoot of the target will be tolerated.

The second reason for the Fed to tighten gradually is that inflation and wage pressures have thus far remained limited, due in part to disruptive technological advances and an ageing population. In fact, there is a feeling amongst policymakers that ‘natural’ real rates have structurally declined – perhaps to as low as 75-100bps, meaning that a terminal rate of 300bps appears plausible. This is certainly good news for Emerging Markets in the long term.

Finally, it is important to understand that it will be extremely difficult to normalise interest rate policy in this cycle to provide sufficient scope for rate cuts alone to tackle the next recession. Unconventional measures such as QE will likely be necessary for many cycles to come. This is particularly true in the US, given that the current administration is also exhausting the capacity for fiscal expansion. The Fed’s ability and willingness to use unconventional measures in the future should result in more gradual rate rises today.

Elsewhere, Bank of England governor Mark Carney said something similar in a

recent press conference, and then of course there is the Bank of Japan, for

which QE is the only option it has left, short of outright money printing.

In the three previous tightening cycles that led to wider EM turbulence since the 1990s, the real Fed Funds rate was much higher than where it is today – typically over 2%. If our view on gradual rate hikes is correct, then there is little reason to worry about overtightening and its impact on EM.

So what about the fundamentals? We have to accept that global liquidity conditions are tightening, albeit slowly. This means that the cost of capital is rising and the competition for it is intensifying. Clearly this has the potential to impact demand for EM assets. It is therefore vital to assess the critical elements that determine investors’ appetite for exposure to EM equities and currencies during a tightening cycle, namely the position and trajectory of current account balances, inflation, real rates, external debt sustainability, and political situations.

Current account positions

Reassuringly, the largest parts of the Emerging Markets universe now run current account surpluses. These net creditor countries are far less vulnerable to a deterioration in short-term fund flows. Two thirds of EM countries are firmly in surplus territory, notably Korea, Taiwan, China, Thailand, Malaysia, Russia and Hungary. Meanwhile, the median current account position in deficit-running EM countries has improved from 3.2% of GDP in 2014 to 1.6% today.

The glaring exceptions are Argentina (5.7%) and Turkey (5.2%), which account for 0.8% of the EM universe. However, with an appropriately attractive level of real interest rates and a sensible fiscal policy, these deficits should be manageable. Free-floating exchange rates can also act as a pressure release valve, unlike in the fixed exchange rate regimes of the 1990s.

Despite this, investors in Argentina and Turkey have taken fright, principally because of a recent deterioration in the terms of trade (oil/agriculture), domestic policy errors, and worsening political situations against a backdrop of tightening US monetary policy. Not all of these factors will be permanent. However, it tends to be true that when short-term portfolio flows exit, a process is unleashed that aims to replace this short-term capital with long-term capital (multinational agencies/FDI) or export dollars. Governments can facilitate or impede these flows through policy initiatives, whilst exchange rates adjust to a new equilibrium. So how far are we through this process?

In Turkey’s case, an improvement in the current account has to come from an improvement in the terms of trade. Encouragingly, the currency does appear cheap. The Lira has been on a deteriorating path for well over five years, losing nearly 60% of its value. On most REER models, it is now at least 25% undervalued. Unfortunately however, any recent improvement in the non-oil trade balance has been more than offset by the rising cost of oil imports (15% of total imports). The one bright spot in 2018 should be tourism (10% of GDP), especially given the massive relative move in the Lira versus the Euro. However, until the oil price surge comes to an end, life will remain difficult.

Turning to the denominator in the current account/GDP ratio, the corporates seem to think that economic growth of 4-4.5% remains achievable this year (vs 7.5% last year). That said, the real estate sector is a problem. The housing stock isn’t moving – no surprise given rental yields of 3% against 15% returns on time deposits. A real estate collapse could certainly be the trigger for a recession. The AKP has thus far managed to prevent this by forcing the construction companies to increase their leverage, but it is questionable how long this can continue. In sum, it is very hard to see Turkish economic growth surprising on the upside, given the prospects for higher rates and the sentiment impact of the current volatility.

For Argentina, we anticipate a material improvement in the current account position, assuming the government can continue on the current path, with the blessing of the IMF. The Peso has fallen to levels last seen in 2015, and now seems fairly valued after adjusting for inflation. Of course, further currency depreciation is likely over the coming months, given that inflation is running at well over 20%. Unfortunately, Argentina is a closed economy, ranking 150th in the world for exports plus imports as a % of GDP. It is therefore unlikely that a dramatically weaker currency will be a major factor in generating economic growth. Crucially however, Argentina has three key macro tailwinds:

- The oil import bill should

dramatically reduce as gas production ramps up in Vaca Muerta, one of the

largest shale reserves in the world.

Tecpetrol, part of the Techint Group, is said to be ramping up

production to deliver an additional 20% of the country’s total gas production

by 2019. YPF and Pampa Energia will not

be far behind.

- Agricultural production (25% of exports) should ramp up into

2019. Adverse weather has decimated

production of soy and wheat harvests this year.

Argentina produced 50m tonnes of soy in 2017, but is expected to produce

just 35m tonnes this year. A normalisation

of production in 2019 should see the trade balance and economic growth improve

significantly. Climatologists point to strong future harvests as recent rains

and the end of El Nino allow production to ramp up again. There is also talk

that Argentina might freeze the soybean tax cut in an effort to put off export

deferrals.

- Argentina has also embarked on a programme of strong fiscal

discipline to help reduce the primary budget deficit. In an effort to reassure

investors, the target for this year’s primary budget deficit has been cut from

3.2% to 2.7%. As investor sentiment recovers, this should allow the central

bank to row back on the exceptional monetary policy response that was required

to stabilise the currency. Thus, real rates could fall from around 12% to more

like 5%.

Given these tailwinds, the current account deficit could move from 5.7% to a more manageable 3.5% in 2019.

In terms of economic growth, corporates now expect 2018 GDP growth of 1.5-2.0%, assuming rates are brought down within the next 3 months. They had expected 3.5% before the drought and the FX crisis.

Inflation and rates

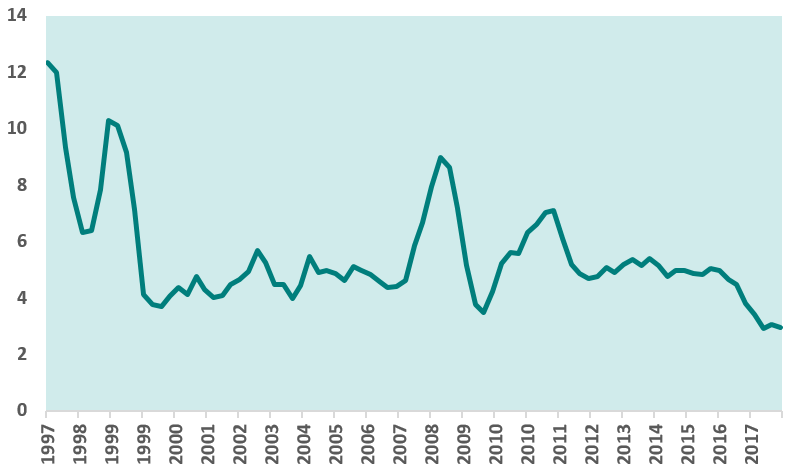

EM inflation rates are now at levels that are more akin to Developed Markets, and are certainly a far cry from the elevated levels of the 1990s. The median rate of inflation for Emerging Markets is 2.2%, while a wider Bloomberg measure sits at 2.9%.

EM CPI

Source: TT International, Bloomberg

Even in countries such as Mexico where we have seen rising inflation, our view is that CPI will now begin to fall.

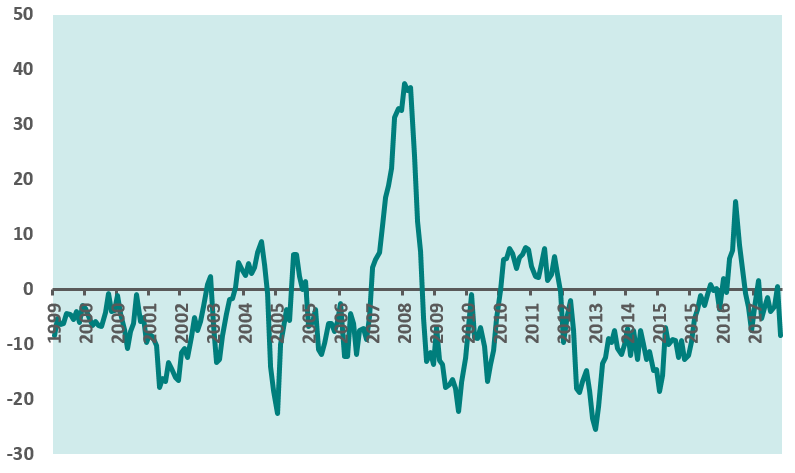

Emerging Markets Inflation Surprise Index is falling

Source: TT International, Bloomberg

Of course, Argentina is one country where a disinflation policy has been slow to take effect, while Turkey seems to lack any credible inflation targeting policy at all.

In Argentina we have a clear case of a central bank determined to follow an orthodox monetary policy in an economy that has not yet normalised. This presents a policy conundrum. In most economies, changes in interest rates are an effective tool, partly due to high private sector credit levels. This is not where Argentina is today. Much of the economy is still dollarised, and private sector credit to GDP is just 15%. Moreover, much of the inflationary pressure is either imported energy inflation or one-off tariff ‘normalisation’, neither of which is affected by tighter monetary policy. By using high rates as a tool to target inflation, Argentinian policymakers have increased local currency debt servicing costs and have kept the real exchange rate artificially high, exacerbating the current account deficit. They have also encouraged the carry trade investor. However, this carry trade has unwound in recent weeks as global liquidity conditions have tightened and inflation targets have proved overly optimistic.

This cycle has to be broken. Thankfully, our meetings uncovered two encouraging developments in this regard. Firstly, Macri has achieved an important step in removing the link between inflation expectations and wages. Nearly all of the 2018 wage settlements will be readjusted to compensate for historic inflation rather than expected inflation. Consequently, if Argentina’s inflation targeting policy is effective, wages can fall more quickly than might otherwise have been the case. Secondly, it appears that the IMF understand the damage that 40% rates have on the economy, and what little use these rates have in tackling the underlying root causes of inflation. They recognise that there has to be less intervention in the FX market, lower medium-term rates, and efforts to tackle the fiscal deficit.

With this in mind, it is also encouraging that Macri has appointed Treasury Minister Nicolás Dujovne to be the main government ‘super’ coordinator (representing 9 ministries) on strategy, setting the stage for a much more coordinated approach between fiscal and monetary policy. The trade off to fiscal cuts is a political one, which we will come on to later. As for the inflation pass through from the FX decline to date, a 40% direct pass through implies that inflation of 25-30% is now likely for 2018, up from consensus expectations of just over 20% six weeks ago. The shock and awe of 10% real rates appears to have brought stability until an IMF agreement can be struck.

For Turkey, the outlook for the inflation targeting regime is highly uncertain. Erdogan has undermined the independence of the central bank and has suggested that only by lowering rates can inflation be bought under control. There is much policy uncertainty given the upcoming Presidential election on 24th June, and absolutely no commitment to reform. Just this week the central bank finally capitulated and raised interest rates by 300bps to the top of the corridor, with little positive impact on the currency. Given recent Lira depreciation and the 11% oil price rise this quarter, it seems reasonable that inflation moves from 10.5% to at least 12%. Inflation will likely then become sticky as recent PPI related impacts (higher gas prices for industrial users) and wage expectations start to bite. Five- and ten-year bonds are yielding 17%, but even they could widen further given the uncertainty.

External debt

Despite the headlines, the debt profile of EM countries is much better today than the common narrative would have you believe. Of course debt levels vary a lot, but vulnerability normally stems from a high proportion of foreign debt needing to be serviced at a time when global liquidity conditions are tightening. Reassuringly, almost 75% of the MSCI EM universe has external debt/GDP levels below 30%. Turkey and Argentina have external debt levels of between 40-50%. In fact, on a net basis, Argentina’s external debt is just 28% of GDP. Turkey’s foreign currency debt is mostly held in the private sector, while Argentina’s is mostly in the hands of the public sector. Of course, we can’t dismiss ANY level of foreign debt exposure during a period of wider capital flight. Whilst this is not our base case, it must be noted that Emerging Market debt funds have seen huge retail inflows, with over $40bn of flows into such ETFs over the past two years alone.

In the case of Argentina, there is a not insignificant figure of $31bn (10% of GDP) of capital and interest payments due over the next 18 months. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the rumoured standby agreement being discussed with the IMF is circa $30bn. In theory this should totally backstop the bond market. We have heard from various sources that other multilateral agencies are being lined up to contribute. Argentina represents an important strategic partnership in South America for the US government. President Trump’s support for Macri was expressed in a tweet during the height of the crisis, which did not go unnoticed. Many think that this show of support will also mean that MSCI will come through with their upgrade of Argentina to ‘Emerging Market’ status. A decision is due in June. Moreover, with Argentina hosting the G20 meeting later this year, it will be seen as even more important to avoid an economic crisis in the country.

We are also encouraged by the situation with private sector leverage. Having met Banco Frances, Supervielle and Macro, there was a strong feeling that NPLs will continue to show little sign of stress, assuming rates are normalised in the next few months. They also believed that 40% loan growth targets look achievable. Therein lies the dilemma for an investor – in the middle of a crisis, the banks are actually seeing positive earnings revisions. All three companies articulated a story of rising net interest margins as they take advantage of the opportunity to fund the government using cheap deposits.

Meanwhile, Turkey has 21% of its total external debt maturing in the next 12 months, a figure close to $180bn. The majority of this debt is held in the private sector. Most corporates have been able to roll their debt so far, albeit at higher interest rates. This situation will ultimately mean stress in the banking system. So where do the NPL risks lie? Turkish banks have 7% NPLs underwritten by the government for any SME lending to the tune of TRY200bn last year and TRY50bn more in 2018. Unsurprisingly, that has boosted bank earnings and does underpin the SME loan books. SME debt is also Lira-denominated. The biggest concern at present is the corporate books, especially given three significant ongoing corporate restructurings. However, after drilling down into the detail of each of these, we believe the private banks are very well collateralised. The big corporate issue is the FX lending mismatch, but we believe this is confined to the energy and construction sectors. With regard the energy sector, again there are government backstops. So what about the consumer? Encouragingly, the consumer is not over-levered (20% loans/GDP), not exposed to FX debt, and only 28% of credit card debt is revolving. Mortgage penetration remains low, and despite our concerns about the real estate market, loan-to-value ratios are low. Of course, we should expect an uptick should the economy contract sharply, but this is clearly discounted in many stocks.

Politics and reform

Finally, we come to politics and reform, probably the most important factor for the most troubled markets. We were struck by just how committed the Argentine government is to the reform programme and how Turkish governance acts as a perpetual overhang to the multiple rating of the market.

It is a given that Macri’s popularity will suffer dramatically following the events this year. Most expect his ratings to trend towards 35% from almost 50% at year-end. Cristina Kirchner has spent the last 10 years discrediting the IMF, so turning to the organisation for help carries an extremely high political cost. Pushing through the increase in tariffs and removing subsidies will further erode Macri’s political support. In a meeting with a political consultant, we heard that if a nationwide vote was held today, Kirchner would command 24% of the vote, ‘moderate’ Peronists 21%, Macri 16% and Maria Vidal (Governor of BA Province and part of the ruling PRO coalition) 19%. This would mean no outright first round victory, and a small possibility that if Kirchner chooses to run, then the huge number of anti-Kirchner voters will have no option other than to choose Macri (assuming he is the PRO candidate, rather than Vidal). The particularly encouraging point from our discussions is that Macri appears to be pragmatic, and should it look like his popularity is still struggling in 2019, it is likely that he would hand over to Vidal (a compassionate conservative) to run for the next election. In other words, Vidal represents a second chance for the current administration to further the reform effort. There is also a possibility that a moderate Peronist candidate could emerge in 2019. Though commitment to reform would be in doubt, nobody we spoke to thought Cristina Kirchner had much chance of winning the next election.

As for Turkey, the working assumption in Istanbul is that Erdogan will be elected President next month and, should AKP/MHP get 50% of parliament, he will return to orthodox policy. There are two risks here. Firstly, it is not clear that they will get 50% of the parliament. If they don't, Erdogan has already threatened to recall parliament again, arguing that it will be unworkable. Turkey certainly doesn’t need months of uncertainty. Secondly, there is a risk that, even if he does consolidate his power, he still won’t implement the orthodox macro policies that Turkey requires.

In conclusion

- Our base case is that Fed policy will remain accommodative

- Emerging

Markets as a whole have less vulnerabilities than they have had for 20 years

- Argentina

and Turkey are clearly unsustainable macro outliers

- Argentina

has a fighting chance to succeed due to an ongoing commitment to reform

- Turkey

remains vulnerable whilst the higher oil price pressures its terms of trade