We outline the main reasons for our Indian overweight in both our Asia and EM portfolios.

Five years ago, Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party won India’s first single-party majority after three decades of fractious coalitions. This victory was based on a promise to usher in the “acche din” – or good days. Modi’s uplifting vision was of an urbanised, industrialised and modernised India, which would absorb millions of young people into the workforce each year, and provide higher living standards for an ever more connected and demanding population. This idea captivated India’s 1.3bn people, a huge number of which were still poor farm workers. Five years later, India has just returned its verdict on whether Modi was able to live up to those lofty ambitions. He was handed an even stronger mandate and will now have a second five-year term to build on his initial successes. But the Prime Minister has no time to savour victory. Indian GDP growth slowed to 5.8% in 1Q19, the slowest pace since 1Q14, amid weak consumer demand and investment. Despite the slowdown, we remain constructive on India as we expect near-term growth to be supported by monetary easing and falling oil prices, while long-term prospects should continue to improve, driven by a transformational programme of structural reform.

Modi’s modifications

While Modi’s reforms have been criticised for causing short-term disruption to the economy, we believe they are critical for modernising India. One of the most important reforms was overhauling the fragmented and unwieldy tax system to create a single, unified value added tax. The so-called “Goods and Services Tax” replaces twenty-nine separate tax systems with one. Previously, businesses optimised the location and size of their operations in various states to minimise taxes. Now they are able to consolidate their operations, improving efficiency and reducing logistics costs. For example, Godrej Consumer Products told us that they were able to save 10-15% of warehousing and freight costs through such consolidation. Moreover, the new tax makes it easier for businesses to compete across states. In this sense it has been likened to the Common Market in the EU, unleashing competition and further improving efficiency. Of course, as with most significant changes, it has been difficult to execute. We expect the government to further simplify this tax framework and perhaps to reduce rates. For example, if New Delhi wanted to support the moribund construction industry, it could lower the tax on cement from 28%, as well as slash heavy fees for property registration. Once fully implemented, the GST should allow tax policing to be completely automated, making avoidance extremely difficult. This should help to further formalise the economy. Ultimately, we expect this vital reform to boost business efficiency and expand the tax base in a country with a tax-to-GDP ratio of less than 12%.

In

addition, the government has also created a new bankruptcy court for the speedy

resolution of insolvency cases. This is a big step in a country where

entrepreneurs, thanks to pliant state lenders, were able to stay on life

support indefinitely. Historically, business owners were guilty of borrowing

too much, assuming they could bribe state-owned banks to lend more whenever

they needed it. This was partly because business owners could force banks to

take haircuts on their loans. With the new Bankruptcy Code, the power has

shifted decisively from the borrower to the lender. Now the banks hold all the

cards as defaulting business owners will lose control of their companies almost

immediately. This should lead to better capital allocation within the economy,

a safer banking system, and a lower cost of financing. As with the GST, the

Bankruptcy Code has experienced teething troubles, with slow progress being

made on some of the cases going through the bankruptcy court. Again, we expect

to see further streamlining of this reform to improve its effectiveness.

While the GST and Bankruptcy Code were the two most crucial big-ticket reforms of national significance, the Real Estate Regulation Act was equally transformative for the property sector. Before this Act, the industry was in disarray. Property developers were taking customer deposits and using them to fund land purchases and other forms of speculation. Consequently, homes were not built and stories circulated of buyers still waiting for their properties to be delivered after 8 years. Following the Act, buyers’ deposits are kept in an escrow account, with funds disbursed to the developer only after specific construction milestones are met. Crucially, developers must commit to a timeline for delivering the property, and face penalties if they do not keep to this timeline. Such regulation is leading to a consolidation of the sector in favour of the more reputable developers that will actually deliver properties to buyers. We currently own several property developers, which should be the key beneficiaries of this trend.

We expect to see incremental improvements in the execution of these measures as entrenching such transformative reforms will be vital to India’s future prosperity. We also expect to see new reforms in the labour market. India currently has a huge number of labour laws – 44 at the federal level and even more for the states. These laws often have conflicting provisions and definitions. Simply being aware of so many laws is challenging for any business. However, the government plans to streamline this into 4 labour codes at the federal level, which are likely to be passed within a year. This promises to significantly reduce the cost of compliance for businesses.

In addition to making progress on reforms, we also expect the government to further recapitalise India’s state-owned banks, which are struggling under the considerable weight of their non-performing loans. These banks account for more than 60% of total bank lending in India, making such a recapitalisation vital to revive growth in the country. We note that the influential Bimal Jalan Committee is about to make its recommendation on the transfer of surplus reserves from India’s central bank to the government. Such a transfer could be in the order of $14-42bn, providing significant scope to recapitalise state-owned banks or increase spending on infrastructure. Indeed, in its manifesto, the Bharatiya Janata party said it would make capital investment of $1.4 trillion in the infrastructure sector over the next 5 years. We therefore expect major projects such as roads, railways, airports, and gas & water grids to get the go-ahead, providing an additional boost to growth.

Stars align above India

Up to this point, we have discussed some of the key decisions actively made by the government to improve India’s prospects. However, there are also factors largely beyond New Delhi’s control that are beginning to align for India.

Firstly, continuity of government and less policy uncertainty should help unleash animal spirits in both businesses and consumers. We believe that investment and consumption have been held back over the past 6 months by worries about the impact of a potential coalition government. With Modi now in power for another 5 years, this overhang has been removed, which should provide a fillip to economic activity.

Secondly, with domestic food prices subdued and the oil price having fallen significantly this year, Indian inflation is firmly shackled. This means that real rates are elevated, providing substantial scope for monetary easing. Indeed, analysts estimate that interest rates in India could fall by nearly 2%. This, combined with liquidity injections from the central bank to improve the transmission of such rate cuts, could drive a significant pick-up in demand, particularly in areas such as mortgages, where cuts quickly take effect. The other key benefit of a falling oil price for a big energy importer such as India is an improvement in the current account deficit. In fact, a $10 fall in the oil price reduces India’s current account deficit by 40 basis points and as a result, the recent pull back in the oil price is very supportive.

Of course, the sharp fall in the oil price is largely due to fears of a global slowdown, exacerbated by Sino-US trade tensions. While India is certainly not immune from these issues (we note that trade relations between India and the US are themselves deteriorating), it is a reasonably insular economy with powerful domestic growth drivers. Consequently, we believe that the Indian market is likely to perform relatively well in a risk-off environment dominated by concerns about a slowdown in global trade and growth. One caveat is that India runs a fiscal and current account deficit, which means it can be vulnerable to capital outflows in times of stress. We feel that this argument is becoming less persuasive as the current account deficit is narrowing due to lower commodity prices. Moreover, from an equity market perspective, domestic investors have doubled their ownership stakes in India’s largest companies over the past 5 years. The majority of the equity in these companies is owned by controlling stakeholders, domestic mutual funds, or the Indian public, with foreign investors owning only about a quarter of it. We believe that this should help to make the Indian market less vulnerable during periods of risk aversion by global investors.

Not only should India be reasonably insulated from a trade war between China and the US, in the long-run it may also be a key beneficiary of it. Vietnam is perhaps the country with the most to gain from a protracted trade war. Its trade surplus with the US jumped 46% in 1Q19 and it has become the preferred destination for companies looking to move their factories out of China to avoid rising labour costs and tariff threats. However, when we speak to companies, they clearly understand that it will be impossible to shift all their Chinese manufacturing facilities to Vietnam. There are well over 100 million low-end manufacturing workers in China. Vietnam simply doesn’t have the capacity to cope with such a huge influx of manufacturing jobs. By comparison, India has a vast population easily able to absorb these jobs. Moreover, the country is intrinsically more compatible with the West in terms of language and democratic political systems. Finally, manufacturers will always be slightly biased towards locating production facilities in a country where there could be significant incremental growth in domestic demand. India clearly fits that description too.

Land of the compounder

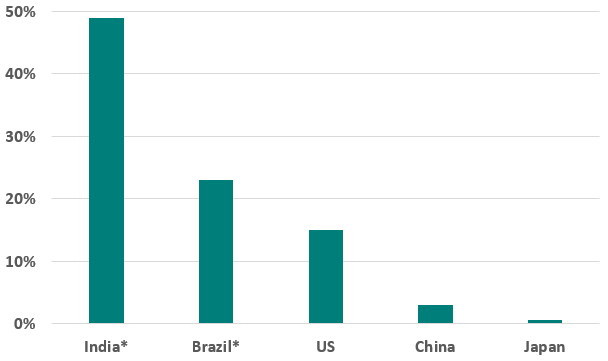

Until now we have discussed some of India’s positive top-down attributes, but we are also constructive from a bottom-up perspective. We believe India is an exceptionally fertile land of compounding stocks. Nearly 50% of the stocks in India’s BSE200 (ex-cyclicals) index have delivered 20-year Compound Annual Growth Rates (CAGRs) of 20% or more. 70% have generated CAGRs of over 15%. The prevalence of such ‘compounders’ in India is not just high in absolute terms, it is much better than other large countries, as can be seen from the chart below.

Proportion of indices that have delivered 20/15% CAGR returns over 20 years

Source: Bloomberg, BofA Merrill Lynch Global Research

*Note: Shows proportion of stocks in India/Brazil that delivered >20% CAGR. Other countries show proportion of stocks that delivered >15% CAGR.

At this point it is worth mentioning some of the exciting bottom-up themes that we have exposure to in India. Firstly, we continue to own several private sector banks. India’s state-owned banks are still reeling from a distressed debt crisis. Private banks are taking advantage of this weakness, capturing significant market share from their state-owned counterparts. In 2011, private banks accounted for just 18% of both deposits and outstanding loans. These numbers have now risen to 28% and 34%, respectively. What’s more, India is exiting a severe credit cycle. As bad loans fall, credit costs should come down and net interest margin should rise. When combined with rapid credit growth, this should drive earnings higher. One criticism that is often levelled at Indian stocks is that they are expensive. Crucially, when we value stocks in India (or anywhere for that matter), we only use higher multiples when we truly believe they are justified by the growth and quality attributes of a company. For example, we are currently willing to ascribe higher multiples to Indian private banks because of the aforementioned market share trends. Indian private sector banks also typically have high ROEs and usually raise capital at a significant multiple of book value, making it accretive in terms of book value per share and EPS.

That said, some of our Indian holdings are optically cheap compared to their regional peers. For example, we own mall developer Phoenix Mills. We are generally positive on the Indian consumer and expect retail sales to rise now that the overhang of the election has been removed. Our crosschecks with many retail names and cinema operators such as PVR suggest that Phoenix is the best managed mall operator in the country and that many businesses are very keen to take space in its malls. As a result, Phoenix has a very high occupancy rate. The malls have also historically shown strong growth in consumption and therefore rents. Looking at its expiry profile over the next two years, there are opportunities for significant upward rental revisions. Moreover, Phoenix did a joint venture deal with Canadian pension plan CPPIB in exchange for a large amount of cash. Thus, Phoenix has been able to fund its growth very cheaply. Despite this strong investment case, Phoenix trades at a discount to other mall operators in the region such as SM Prime. It also trades at a discount to consumer stocks in India more generally. Finally, the company is a beneficiary of falling interest rates.

In addition to Phoenix Mills, we own several property developers that will also benefit from lower interest rates. Affordability levels are already near 10-year highs, but should improve further as rates come down. Moreover, by hounding out the less reputable developers, the Real Estate Regulation Act is reducing housing supply. As a result, inventories are falling and sales are improving. We expect prices and ultimately profits to follow.

One of the key differentiating elements of TT’s investment process is that we integrate both top-down and bottom-up research in an attempt to generate alpha for our clients. Our most successful investments tend to occur when positive top-down and bottom-up factors coalesce. We believe India currently offers this attractive combination, and continue to be overweight in both our Asia and Emerging Markets portfolios.