Japan’s banks have struggled to recover from a financial crisis that began in the 1990s. We argue that banks in Europe now face similar challenges following another debt-fuelled bubble.

Frankfurt's financial district. Source: Wikimedia

“New Year rally expected on Tokyo market next week.” So read a typically jubilant Japanese newswire headline on December 29th 1989, the day that one of the world's biggest asset-price bubbles reached bursting point. Almost 30 years later the Japanese are still paying the price for such hubris. The Nikkei 225 index, which peaked at 38,916, now languishes at less than half that level. Japan's economy, stalked by the spectre of deflation, suffered two “lost decades” in which it barely grew in nominal terms. Meanwhile, Japanese banks were forced to endure endless private sector deleveraging, soaring non-performing loans (NPLs), and a gradual erosion of net interest margins. Consequently, the value of Japanese banks declined steadily from 3.5x book to around 0.5x today. Studying Japan’s experience allows us to travel back to the future in order to glimpse what pressures Europe’s financial system could face after a similar debt-fuelled bubble.

The scale of Japan’s bubble was truly epic. After it burst, the country’s banks faced a perfect storm of stagnating private loan demand, soaring NPLs, and falling net interest margins. This led to a prolonged period of weakening profitability for Japan’s banks, from which they are yet to fully recover. Unfortunately for Europe, its banking system is beginning to show signs of turning Japanese.

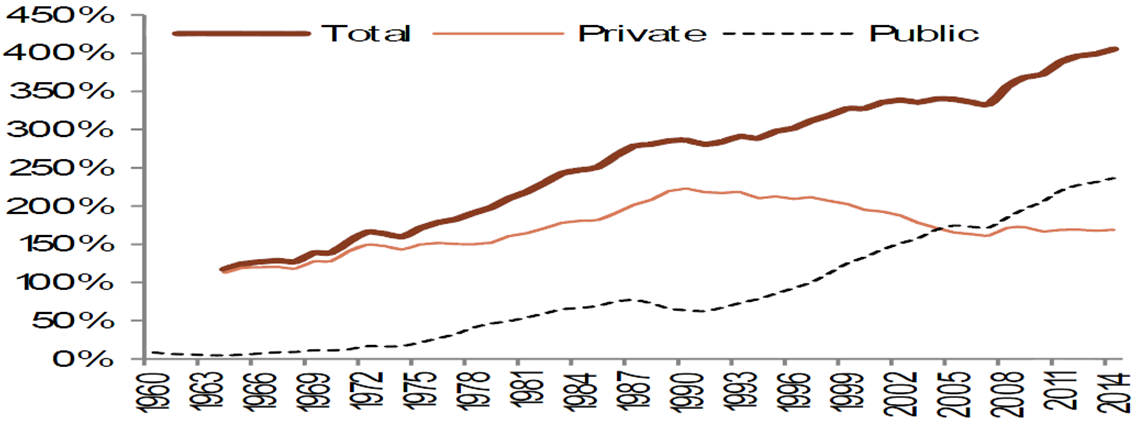

As can be seen from the chart below, private sector loan demand in Japan peaked shortly after the bubble burst. It then began to wane steadily.

Japanese debt as % of GDP

Source: Macquarie

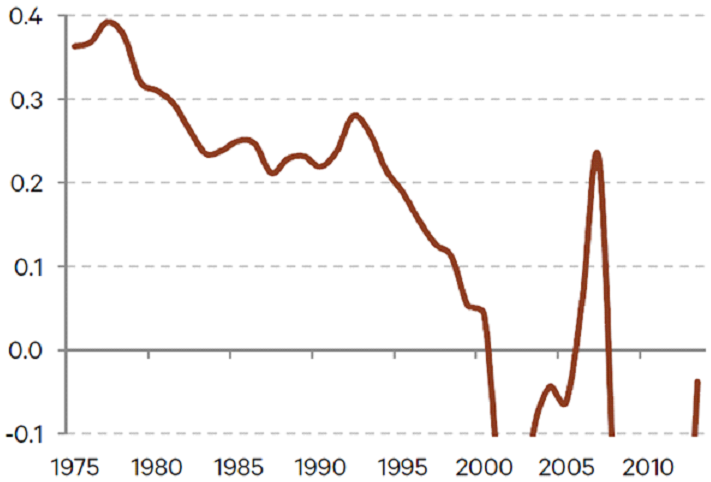

The reason for this was two-fold. Firstly, return on debt collapsed, reducing the incentive for people to borrow.

Incremental return on debt in Japan

Source: Berenberg

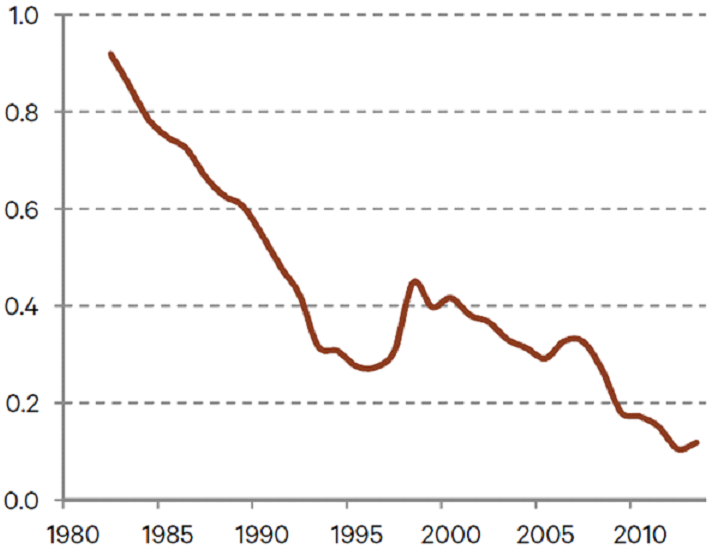

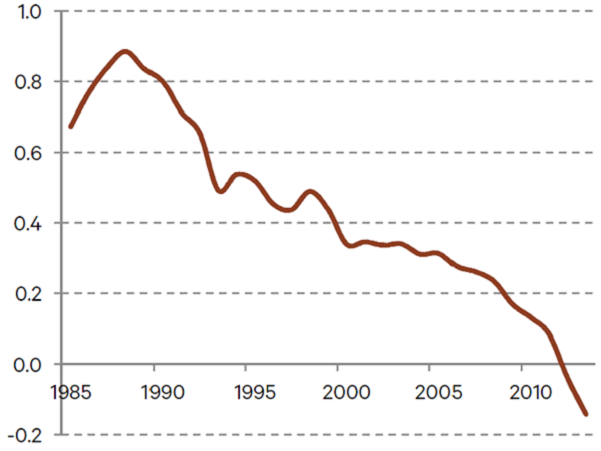

Ominously, a similar trend can also be seen in Europe.

Incremental return on debt in France

Source: Berenberg

Incremental return on debt in Spain

Source: Berenberg

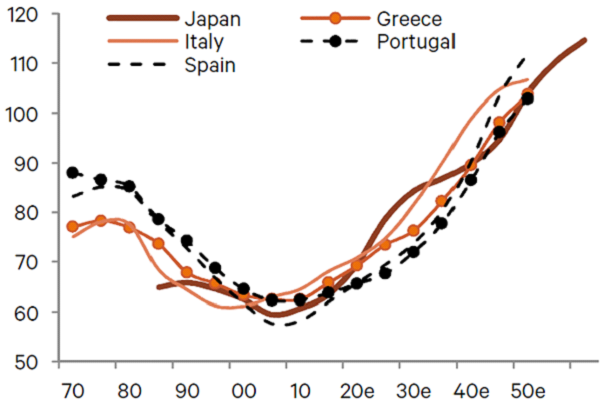

Secondly, Japan’s credit bubble coincided with the spending peak of the post-war baby boomer generation. Consumers tend to reach peak spending in their mid-40s as they trade up their homes and cars and spend on their children. For Japan’s baby boomers this occurred at the height of the debt-fuelled bubble. But just as the bubble burst, these people were entering a later stage in the consumer life cycle. This stage is associated with lower borrowing and spending as consumers begin to save more for retirement. Unfortunately, the same demographic trends are playing out in Europe, particularly in the periphery, which is ageing almost as rapidly as Japan.

Total dependency ratio – non-working age population as % of working-age population (Japan data lagged by 10 years)

Source: Berenberg

Credit growth in Europe is anaemic at best, and in fact is negative in the periphery. The Japanese experience suggests that there is little prospect of a reacceleration, given the continent’s ageing population and a falling return on debt.

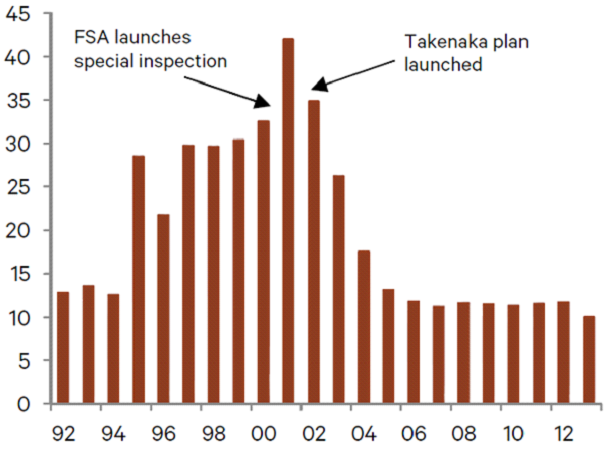

In addition to stagnating demand for credit, Japan’s banks also had to contend with soaring NPLs. Banks hid the true extent of the problem for a decade, until the Japanese regulator forced them to fully recognise their NPLs and offload a prescribed percentage of them over time.Japanese banks’ NPL stock (trillion yen)

Source: Berenberg

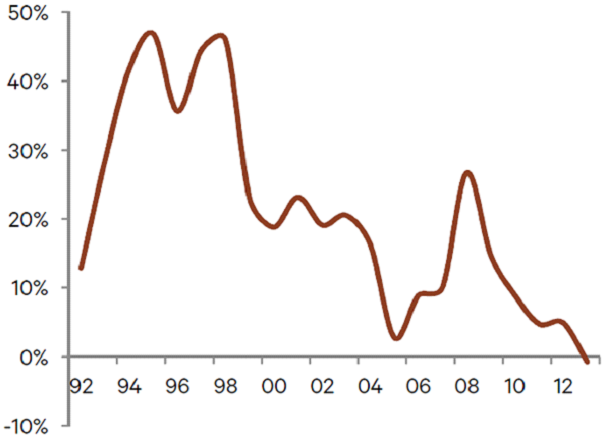

The resultant losses were severe, and many banks needed to be recapitalised at the expense of equity holders.

Japanese banks’ loss on disposal of NPLs (as % of NPLs)

Source: Berenberg

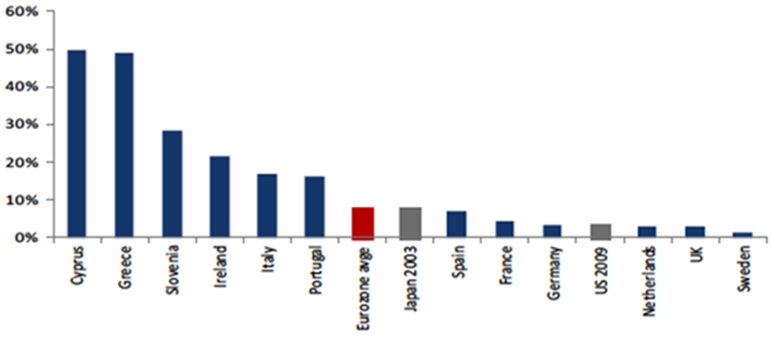

This painful process is yet to be fully played out in Europe. Eventual losses will be largest in the periphery, which accounts for 32% of Eurozone GDP but 67% of non-performing exposures – exposure to loans that are unlikely to be repaid in full. Cyprus and Greece are the worst offenders, but non-performing exposures in almost all peripheral countries remain higher than in Japan following its version of the Asset Quality Review in 2003.

NPEs are higher in the periphery than after the clean-up of Japanese banks in 2003

Source: EBA, company data, Federal Reserve, BoJ

The European banking regulator recently published a consultation paper in which it required banks with NPL ratios above the European average to reduce them within a set time horizon. It also requested that banks adopt strategies to assist with the recognition and reduction of NPLs, including implementing better IT infrastructure. Whilst clearly a positive step, in the short term these measures could force NPL disposals at below book value, damaging capital ratios. Put simply, Europe is not done with bank recapitalisations.

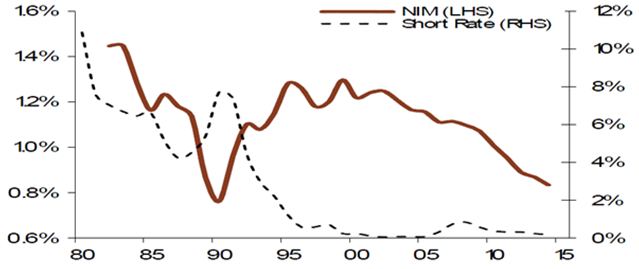

Alongside rising NPLs and subdued demand for loans, Japanese bank profitability was also impaired by falling net interest margins. Contrary to popular perception, net interest margins were not always terrible in Japan. After the bubble burst and interest rates were slashed, bank margins initially rose.

Japanese net interest margin versus short term rates

Source: Redburn

This was because the short term rates that banks paid their depositors fell immediately, whereas the longer term rates they charged on their loan books took time to re-price downwards. However, banks will always struggle to push the rates they pay depositors much below zero as people can simply withdraw their cash instead of paying the bank to hold it. Hence, as Japanese interest rates approached zero, the country’s banks faced increasingly ‘sticky’ costs. Meanwhile, the rate at which banks could lend continued to fall as the yield curve flattened and competition to make new loans intensified amid stagnating demand for credit. Thus, net interest margin – the key driver of banks’ profitability – was slowly eroded.

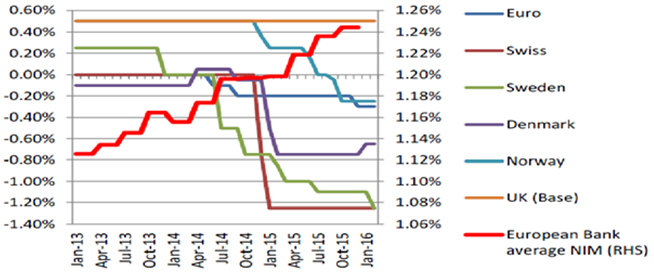

As in Japan, the initial impact of falling interest rates has been positive for European banks due to lower deposit rates, stabilising asset prices and decreasing NPL provisions. Indeed, despite numerous rate cuts to stimulate Europe’s flagging economies, net interest margins have been expanding.

European banks’ average net interest margin

Source: Redburn

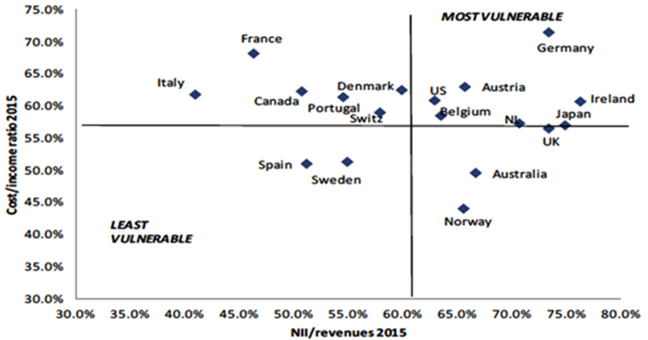

But now that interest rates are negative and the yield curve continues to flatten, European banks face an insidious erosion of profitability. In some ways they are more vulnerable than their Japanese counterparts because they are heavily reliant on customer deposits, which cannot re-price below zero, and operate in highly fragmented markets, meaning stiff competition will likely depress loan prices. As can be seen below, they also derive 60% of their revenue from net interest income and have relatively high costs.

European banks rely heavily on net interest income for revenue and have relatively high costs

Source: ECB, National Central Banks

In fact, European banks’ costs have increased by 7% since 2008: there are too many branches, retirement packages are expensive, and the benefits of digitalisation and outsourcing have not yet been realised. To mitigate the impact from negative interest rates, European banks therefore need to aggressively cut costs through internal restructuring and industry consolidation. Another option would be to exploit additional revenue sources such as account maintenance charges and ATM withdrawal fees. A further possibility would be to re-price loans higher. But this seems less likely as yields already exceed those in many other countries and the European Central Bank is keen for low interest rates to be passed on to the end consumer.

Key lessons

There are three key lessons from Japan’s experience that are pertinent for Europe and its banks. Firstly, a crisis is not over until the banking system has fully recognised bad loans and replenished capital. Secondly, there is a profound shift in behaviour following a crisis, which impairs banking sector profitability for many years. Finally, demography is an underestimated influence on consumption and borrowing behaviour. Let us address each of these in turn.

The critical lesson is that it is not until the banking system has written down NPLs and adequately capitalised itself that it is safe to invest in most banks. Until then equity is steadily eroded and conviction in the quality of bank books remains low. In Japan, banks and politicians refused to address the NPL problem for many years. It wasn’t until the Takenaka reforms forced banks to write down loans to market clearing prices and liquidate NPLs that asset prices finally stabilised. Ireland and Spain have made substantial progress in deleveraging and uncovering latent NPLs, but the same cannot be said for many other European countries including France, Italy and Sweden. Once the deleveraging process begins, it often uncovers further bad loans and reveals the true value of assets. Only after that can bank investors have confidence in stated book and loan values. Until then large discounts are likely to be applied to official valuations. Moreover, given the scale of bank balance sheets relative to equity, even small changes in perceived asset and book values are likely to cause wild swings in equity valuations. Until the banking system is confident it is solvent and well capitalised, the primary concern will be survival rather than maximising returns. This suggests continued downward pressure on leverage ratios – and hence on earnings power.

The second important lesson is that in the aftermath of a debt-fuelled bubble the willingness of borrowers to increase debt remains very low for many years. Consequently, economic activity is subdued, resulting in low and flat yield curves. At the same time, people choose to save more, causing the deposit base to swell. This puts pressure on banks to earn a return on these costly deposits, which is extremely challenging in an environment with limited demand and weakening prices for loans. If the Japanese experience is repeated, ‘sticky’ deposit costs and falling net interest income will lead to a steady decline in core profitability at most European banks.

The final lesson from Japan is that demographics play an important, often underestimated role in determining consumption and borrowing behaviour. In Japan the credit bubble peaked alongside the post-war baby boom generation and the private sector has been steadily deleveraging ever since. The same trend is evident in Southern Europe. As a population ages, levels of consumption, risk taking and debt all begin to decline. Consumers already have homes, cars and other material possessions and rather than accumulating more are focused on downsizing or sustaining what they already have. These demographic headwinds make it very difficult to stimulate spending or borrowing. Thus, there is little incentive for companies to grow capacity and economic activity remains relatively soft as businesses adjust to a future of lower volumes.

Investment implications

Given the challenges outlined above, we remain underweight European banks in all our portfolios. However, there are still some compelling investment opportunities in the sector.

For example, we own Belgium-based KBC Group and Netherlands-based ING Group, two banks that are well positioned to counteract net interest margin pressure. We are particularly attracted by their high capital ratios and sustainable dividends. Furthermore, they operate in consolidated markets, which gives them pricing power, and in economies with better than average loan demand.

In addition, with economic growth in the Eurozone likely to remain relatively subdued, we own Erste Group Bank, which offers exposure to more dynamic emerging economies.

Conversely, our portfolios remain significantly underweight domestic banks in Southern Europe, particularly Italy, where we expect substantial losses and recapitalisations as NPLs are gradually recognised.

Elsewhere in the Financials sector, we own Spanish non-life insurer Mapfre, which is benefiting from improving insurance prices in both Spain and the US. The company has implemented a long term management incentive plan tied to profitability targets, which means that management and shareholder interests are now directly aligned.

Nothing in this document constitutes or should be treated as investment advice or an offer to buy or sell any security or other investment. TT is authorised and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).