A summary of our recent webinar discussion between China Portfolio Manager Marco Li and Dr Ma Jun, former Chief Economist of the PBOC.

On 1st July 2021 China celebrated the 100-year anniversary of the founding of its Communist Party. Since then there has been a period of heightened volatility for Chinese risk assets, driven by a combination of sweeping regulatory changes, a COVID-related economic slowdown, and many industry-specific policy adjustments. Clearly it is more important than ever for investors to understand the Chinese Communist Party in order to decipher the meaning of these actions and determine the implications for the future. To this end, TT recently hosted a discussion with Dr Ma Jun to help elucidate the roadmap for the Chinese economy and provide some insight into the areas that policymakers are focused on. Dr Ma is currently President of the Institute of Finance and Sustainability, a policy think tank based in Beijing. He was formerly the Chief Economist at the PBOC and a member of the Monetary Policy Committee. He has held many titles in the green finance space, including Co-Chair of the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group, and Chairman of China’s Green Finance Committee and the Hong Kong Green Finance Association. He is also an advisor to TT International. Below we summarise the discussion between Dr Ma and Marco Li, Portfolio Manager of our China Focus strategy and senior member of our Emerging Markets team.

Marco Li: please could you start by giving us an overview of the key recent developments affecting the Chinese economy?

Dr Ma: they key recent developments have been power cuts and pressure in the real estate sector, most notably at Evergrande. These issues have led many agencies to revise down their GDP growth forecasts to 4-5% YoY in 4Q21. The government is probably looking to achieve 5.5% growth next year, but this may not be achievable if these issues worsen. Investors are clearly less optimistic than the government on growth.

There are several reasons behind the power cuts. Firstly, other major exporting countries that were serving as manufacturing bases are struggling due to COVID. A lot of the orders are finding their way to China, which is having to use more power to supply these goods to international markets. Secondly, the weather has played its part. In some areas of the country, extreme heat has led to a spike in demand for power from air conditioning units, while in other parts of the country, a lack of wind has rendered turbines unable to generate sufficient power supply. Thirdly, coal prices have surged to a point where power companies are beginning to cut production as the marginal cost is simply too high to be profitable. Finally, the government has a policy known as “dual control of energy consumption”, which looks to limit the energy consumption and energy intensity of each region. Previously these controls were imposed on an annual basis, but are now implemented each quarter. With many regions set to exceed their targets for this quarter, they have begun to cut power.

In my view such power cuts have been exaggerated by the media. Not only are they likely to be a small drag on GDP of just 0.1-0.15%, but they are also likely to be temporary. Indeed, exports should normalise as the COVID situation improves in other manufacturing bases, while the weather issues are unlikely to persist. Meanwhile, power companies can pass on the higher cost of coal to consumers and are already requesting the government’s permission to raise tariffs. Finally, dual control is a blunt policy instrument as it considers total power supply rather than simply focusing on the dirty coal-fired power supply. This seems misguided as the production and consumption of renewable power should be encouraged. I have therefore recommended to the government that it scraps the dual control mechanism and makes it more refined in order to only control the dirty power consumption.

If power cuts have arguably been overplayed by commentators, an economic shock related to the real estate industry is certainly an area that needs to be watched carefully, given the importance of the sector to the Chinese economy. The origin of the present tightening in the sector was the government’s aim to prevent bubbles in the real estate market and ensure that properties are for people to live in rather than speculate on. These are clearly good intentions, but the actual implementation involved a plethora of tightening measures in an uncoordinated manner. Many government agencies enacted policies simultaneously – some tightened lending to developers, some tightened mortgage lending, some tightened supply, while others tightened demand. This led to a very complex and confusing situation for the entire market. Several developers such as Evergrande are now facing big cash flow problems and are subject to default risk. I believe that the government will need to relax these policies soon. If Beijing keeps such tightening measures in place for too long it could have serious unintended consequences. Indeed, there would be a contraction in real estate development, which would have major spill over effects in many other sectors, from construction machinery and materials to furniture and electronics. Moreover, there are financial risks as banks have significant exposure to the sector. Most importantly for the Chinese Communist Party, there are also risks of social disorder. Some developers have pre-sold these projects to buyers. If they were to default then the buyers may well protest against the government. They could be joined by the tens of millions of construction workers and other suppliers that would not have be paid for their work. I therefore believe the real estate tightening measures will be loosened.

The final recent development worth mentioning is on the common prosperity policy. Over the past few weeks the discussion on common prosperity has evolved into more specific items such as whether China should introduce property and inheritance taxes as a way to equalise income and wealth. My personal judgement is that a rushed introduction of property taxes in many cities is unlikely. The government is aware that the real estate market is already under pressure, and such taxes would exacerbate the situation. Similarly, the macro consequences of an inheritance tax would need to be fully considered before any introduction. For example, harsh estate taxes could lead to outflows of capital, with wealthy individuals shifting assets overseas to lower tax jurisdictions. My view is that the more effective instrument for common prosperity is an equalisation of public services, most notably high-quality education. By ensuring that poorer rural areas have access to high-quality primary and secondary education so that children will have the opportunity to attend college and find good jobs, we should enhance social mobility.

Can you help us understand why regulatory scrutiny has increased so much in such a short space of time?

A lot of the recent regulatory changes had been discussed and planned by the government for some time. However, Beijing was keen to ensure that there were no nasty surprises in the form of a market correction or major financial risks in the run up to the celebration of the Chinese Communist Party’s 100-year anniversary on 1st July 2021. Thus, many regulatory measures have been introduced after that event. The key political consideration behind many of these major policy shifts is social equality. Over the past 40 years the party has emphasised market efficiency. Consequently, lots of social pressures are building because income and wealth distribution have become too unequal. Consumers are complaining about being exploited by monopolies. Young couples are complaining about education and housing costs being so high that they are unable to afford having children. The government has reacted by considering the social implications of many issues, including certain businesses that operate in the social space. For example, the education sector is considered to be largely a public service. If areas such as this are monopolised by a few private companies that seek only profitability, then they could be distorted. Similarly, the real estate sector is regarded as having many social spill over effects because high property prices can marginalise manufacturing and discourage young innovators from moving to the big cities. Ensuring education and property costs are manageable also feeds into China’s three-child policy. Another example is the vehicle-for-hire industry where many companies such as DiDi hired vast numbers of drivers without contracts. The government views this as a way of avoiding paying the necessary social security contributions. Going forward, companies will need to give far more consideration to their corporate social responsibilities, otherwise they will likely face greater regulatory scrutiny.

How does this new regulatory regime apply to internet and big tech companies – will they effectively become utility-like businesses with permanently lower ROEs?

The big tech companies certainly made significant contributions to technological innovation and financial inclusion. They are undoubtedly making people’s lives much easier, but at the same time they are generating a lot of negative social reactions within China, and are beginning to monopolise certain practices, using data in a way that benefits their businesses at the expense of consumers. These issues have been understood for several years and needed to be addressed. Moreover, both the general public and the government feel that the owners of these businesses have grown very wealthy and need to contribute back to society, whether voluntarily or not. Like other companies, big tech is under pressure to demonstrate that it is committed to social equality and corporate social responsibility. With this is mind, Tencent and Alibaba have pledged RMB50bn and RMB100bn respectively, setting up funds to support social and environmental causes. These companies are likely to face higher labour costs and charitable donations going forward.

Once corporate social responsibility becomes a more integral part of their DNA, will these companies face less regulatory scrutiny?

Many of the new social rules are yet to be formalised. These companies need to anticipate how the rules will evolve. This will require hiring ESG teams to predict issues that could emerge and how the government will react to social pressure to regulate these companies in the future. They will need to study the international experience of how other countries have handled ESG issues to prevent such problems happening. If they take pre-emptive action then they are less likely to face such harsh regulatory scrutiny.

Many investors have watched the regulatory crackdown spread from education to big tech and areas such as data security. What other sectors should investors potentially be worried about that have perhaps ‘over-earned’ or paid insufficient attention to social equality?

Healthcare is a risky area from this perspective because the industry itself clearly has many social spill over effects. The pharmaceutical manufacturers often earn very high margins and will likely need to think carefully about the legitimacy of being so profitable. Hospital groups, many of which do not make significant profits, are less likely to face additional regulatory scrutiny.

On the geopolitical front, the recent release of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou points to a slight thawing in Sino-US relations. Would you agree and is this likely to continue?

We’re certainly seeing signs of improvement. The release of Meng Wanzhou meets one of the Chinese demands given to the US a couple of weeks ago. Meanwhile, China’s pledge to stop overseas coal financing could be viewed as meeting a US request. John Kerry, the US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, has visited China several times and specifically raised this issue. So both sides have conceded.

There may be opportunities for relations to improve further. For example, the US is concerned about Afghanistan becoming a more significant base for terrorism. China not only has access to Afghanistan’s leaders, but it also has an interest in containing terrorism in the country as it has substantial assets there. Areas of mutual interest such as Afghanistan could be catalysts for renewed US-China collaboration. Another example is trade tariffs. With the US experiencing higher inflation, there is an economic rationale to cut tariffs on certain items to help reduce CPI and bolster Chinese exports.

If an easing of certain tariffs is the logical next step, how far away do you think this could be? Could we even get to a point of having warm relations where the two countries potentially work together on issues such as the green infrastructure buildout in the US, or the easing of tariffs on Chinese polysilicon producers?

It is too early to judge on specific items and timings, but the general direction is that both sides appear to be looking to remove tariffs on certain items that are not politically sensitive or defence related as a first step. At the same time, there could be a resumption of intellectual/scientific exchange to some extent.

Could that have any positive economic impacts in the medium-term?

It is too uncertain to judge the extent to which relations will improve. But even if they do, the overall impact on the Chinese economy is likely to be small as the Trump tariffs did not have a big effect compared to initial expectations.

You mentioned that Chinese exports are likely to slow as other manufacturing centres normalise after COVID, what does that mean for China’s currency and capital flows over the next 12 months?

There shouldn’t be a huge impact on the currency or capital flows. Export growth has been very strong until now. I hear forecasts of 10% YoY growth in the fourth quarter, which would represent a slight slowdown, but a manageable one. However, if the real estate issues remain unresolved then this could certainly put downward pressure on the RMB as the sector is such a significant part of the economy. This is what I’m most concerned about in the near-term.

On that point, what do you think the eventual outcome will be for Evergrande?

There are several scenarios, including arranging new shareholders for Evergrande, which will mean that the company won’t go bust. Another option is to encourage the purchase of Evergrande’s assets by other developers and local governments. Crucially however, even if Evergrande is rescued, if the government continues to apply significant pressure to the real estate sector, it will not solve the problem and more developers will become distressed. China needs to have an effective policy mix to stabilise the entire sector.

Privately-owned enterprises (POEs) have faced widespread regulatory scrutiny. Do you think this is a temporary phenomenon or is this a structural issue that caps the upside profits on private companies versus state-owned enterprises (SOEs), thereby reducing long-term returns?

Some of the POEs feel they have been specifically targeted by the new regulations. Although it may appear that way at first glance, it is simply a function of the fact that SOEs, by their very nature, were more closely aligned with the government’s overarching aim of improving social equality. Indeed, SOEs were originally designed to bear some social responsibilities. For example, state-owned power companies are required to supply power to rural areas, while state-owned banks are expected to open branches in remote communities, despite them not being profitable. By contrast, POEs are just seeking profit maximisation, even to the detriment of consumers. The government is not intentionally targeting POEs, but simply trying to ensure that all companies are more aware of their social responsibilities. The one notable exception is data security, where the government is keen to ensure that sensitive and consumer data is not controlled by private companies, where it may be used in a way that’s not in the best interests of the general public.

We have positioned our portfolios to have significant exposure to industries that enjoy clear policy support, most notably the environmental thematic. Are there other areas of the economy that the government is keen to support?

There are two big themes that the government wants to support. One is the green transition, including electric vehicles, batteries, carbon capture, and other decarbonisation technologies. By my calculation this now accounts for 25% of Chinese FAI. The other big category is ‘hard technology’. China is looking to enhance its internal capacity to innovate, partly to avoid facing a bottleneck that may be imposed by unfriendly countries. As such, the government wants to promote the invention of new hardware that can be the pillars of technological advancement. This idea spans a range of sectors, including power generation, autos, aviation and telecoms.

Thinking out to 2022, we have highlighted the downside risks from the real estate sector overhang. What are some of the upside risks that could materialise? For example, we have seen a serious correction in Chinese equities. Will this mean that monetary and fiscal policy remain more supportive than expected?

We will see stronger infrastructure spending momentum, partly because the local government bond issuance is required to increase sharply from the low level it registered in the first half of this year. The other major policy package that is going to be announced is called “1+N”. It is part of the carbon neutrality roadmap and is currently being drafted by the National Development and Reform Commission. “1” refers to energy, while “N” refers to building, transportation, manufacturing and many other sectors. Each of these sectors will have a roadmap that will specify the government’s multi-year targets and policies that are designed to support them. Once these roadmaps are released, they should generate a lot more investor interest in specific areas of these sectors.

Marco Li’s reflections on the discussion with Dr Ma.

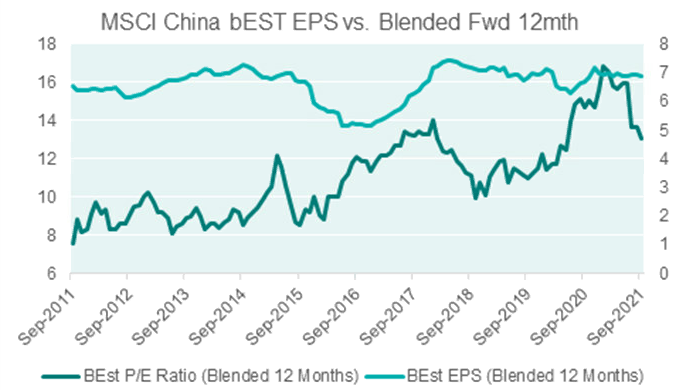

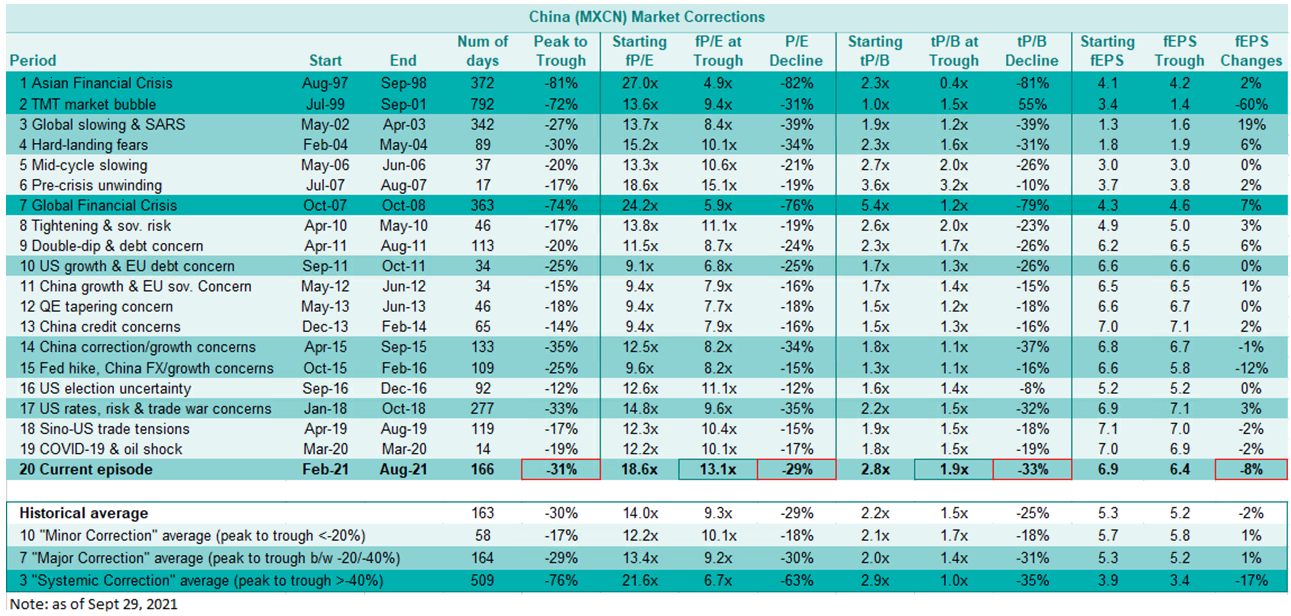

The discussion touched on several key issues, including the rationale for the recent regulatory regime shift, geopolitical relations, as well as risks and opportunities for investors in China. In our view, nothing in the discussion suggested that there will be a ‘hard landing’ for the Chinese economy. Despite this, as well as the fact that corporate earnings remain remarkably stable, fears over regulation have led to a sharp sell-off in Chinese equities that is already as severe as previous ‘major’ corrections in both magnitude and duration – please see the charts below.

China EPS vs P/E ratio

Source: TT International

China market corrections

Source: TT International

Some of the actions we have been taking in our China, Asia and EM portfolios in recent weeks, partly as a result of our ongoing discussions with Dr Ma include the following:

- We have continued to shift our exposure away from internet/big tech into areas that enjoy clear government policy support, most notably green tech. It is worth noting that the surge in coal prices will only serve to accelerate the adoption of renewables. Indeed, renewables such as solar have already reached grid parity.

- We have added slightly to some of our Property Management Services positions as there will likely be further consolidation of the sector. For example, Country Garden is acquiring two services companies (R&F Property Services and Fantasia), both of which are in financial distress.

- With regard to low birth rates and hospitals likely avoiding additional regulation, our China fund owns Jinxin Fertility Clinic.

- Given that the power shortage should lead to increasing demand for energy storage, we have added to Pylon Technologies and battery players such as EVE Energy.

- On e-commerce we are waiting for the impacts of the power outage to normalise before adding, mainly because there is likely to be a production shortage of goods, which may lead to weaker Singles’ Day sales.

- Given that exports are likely to slow as other manufacturing bases normalise following COVID, our China fund has sold out of Viomi, which exports robovacs to the US via Amazon. The fund also trimmed electrical appliance manufacturer Midea for similar reasons.

Nothing in this document constitutes or should be treated as investment advice or an offer to buy or sell any security or other investment. TT is authorised and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).