TT discusses what Abenomics Mark Two could mean for Japan’s economy and its equity markets.

TT’s recent research trip to Japan suggested that there could be a concerted effort to revitalise Abenomics. We assess how effective Abe’s flagship programme has been so far, before discussing what Abenomics Mark Two could mean for Japan’s economy and its equity markets.

When Shinzo Abe swept to victory in 2012, he inherited an economy that had stagnated for two decades. Measured in yen, Japan’s GDP was smaller in 2012 than it had been in 1994. Twenty years of fiscal deficits had failed to lift the economy out of this rut, leaving the government with a debt burden well over 200% of GDP. Abe recognised that without restoring economic growth and keeping it elevated for years, Japan’s debts would likely become unmanageable. To avoid this fate, the new Prime Minister proposed ‘Abenomics’ – a bold plan of attack consisting of three ‘arrows’. The first was expansionary monetary policy, aimed at stoking inflation and weakening the yen. The second was fiscal stimulus, aimed at supporting the Japanese economy in the short run and at fiscal stability in the long run. The third was structural reform, aimed at raising investment and trend growth.

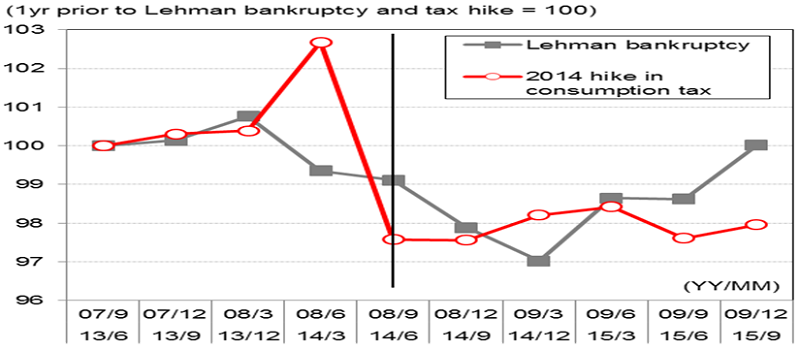

In the two years immediately following the start of Abenomics, Japan’s equity markets soared, the yen weakened, and corporate profits rose. However, economic growth failed to turn decisively positive and companies remained reluctant to increase their domestic investment. Meanwhile, consumption continued to be held back by demographic headwinds and an ill-timed VAT rise, which left consumers shell-shocked and stalled the recovery. Indeed, as the graph below shows, the consumption tax hike had a similarly devastating effect on Japanese consumers as the Lehman crisis.

Impact on consumption of VAT hike and Lehman crisis

Source: Macquarie

As time went by, the consensus view crystallised: Abe’s famous three arrows had missed their target. Monetary policy was constrained by the lower bound of nominal rates, fiscal policy was limited by the size of public debt, and a lack of agreement on structural reforms had undermined their effectiveness. Consequently, there is now widespread scepticism about Abenomics, with foreign investors having sold over $45bn of Japanese equities so far this year.

We believe that such a downbeat verdict on Abenomics Mark One is premature. Investor scepticism could even prove to be a lucrative investment opportunity as our recent research visit suggested that there will be an attempt to revitalise Abenomics. This would have important ramifications for Japan’s economy and its equity markets alike.

First arrow

Our

meetings in Tokyo revealed a strong appetite for further monetary stimulus. The

adverse reaction to negative interest rates has clearly wrong-footed Kuroda,

Governor of the Bank of Japan. The fact that this controversial policy was pursued in the first place shocked many inside and outside the BoJ, including us. Only days before, several insiders at the central bank intimated that this policy was off the agenda due to fears of damaging the monetary transmission mechanism by crimping banks’ profitability. Indeed, Japanese borrowers have not felt the full benefit of ultra-low interest rates because of high street banks’ unwillingness to lend. By shrinking the net interest margin of Japanese banks, negative interest rate could further discourage banks from lending, undermining the effectiveness of monetary policy.

It remains to be seen how the economy will respond to negative rates, which could either stimulate extra investment or reinforce the deflationary mindset. Early indications are that they are boosting the property market and related investment, a theme that we have tried to capture in our portfolios. Negative rates have also encouraged life insurance companies and pension funds to increase the percentage of foreign assets in their portfolios.

Given the severe criticism of negative interest rates, as well as the current limitations on buying more Japanese Government Bonds, it seems likely that any additional monetary easing will largely come in the form of equity purchases. There may also be indirect purchases via Japan’s state pension fund and postal insurance savings. This could trigger a sharp shift in sentiment, though it is important to recognise the diminishing returns associated with these ‘big bazooka’ moves.

Second arrow

We also expect the second arrow of fiscal expansion to be shot again, perhaps with greater force. The recent earthquakes in Kumamoto provide the political cover for Abe to postpone the next consumption tax hike. This is a key concern for the market, given the disruptive effects of the previous VAT rise. Moreover, earthquake reconstruction and a sluggish economy provide the justification for a supplementary budget of c.2% of GDP. There is growing talk of the government issuing near zero coupon perpetual bonds, to be bought by the BoJ. As eminent economist Professor Joseph Stiglitz pointed out in a recent conversation, this would represent ‘QE to infinity’. Other proposed fiscal policy moves include a tax on retained earnings to further encourage the deployment of unproductive cash languishing on Japanese corporate balance sheets.

Third arrow

The consensus appears to believe that progress on the third arrow of structural reforms has stalled. Our research suggests otherwise.

For many years poor demographics have been Japan’s biggest structural barrier. The working age population is falling by 800,000 each year, and this will likely continue for several decades. Supply-side reforms must find a way to arrest this decline, particularly because importing workers is made difficult by the traditional Japanese aversion to immigration. However, recent meetings with the Ministry of Health and Welfare, labour market economists, and Japanese business lobby group Keidanren all suggest that Japan’s policymakers will attempt to solve the country’s demographic challenges by increasing the workforce participation rate for women and the elderly.

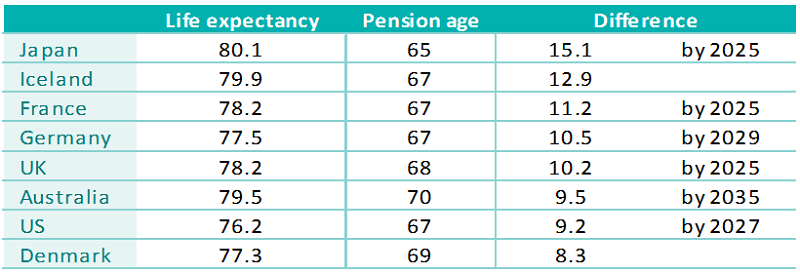

This could have a dramatic impact as Japan’s long life expectancy and early retirement age mean the country has a huge number of pensioners that are still able to work.

Comparison of future life expectancy and pension eligibility age (male)

Source: OECD Pension Outlook 2012

Meanwhile, the labour force participation rate of married women remains virtually unchanged from 1985 at around 20%. In order to encourage people from both groups back into the workforce, it is essential to increase the provision of childcare and improve care of the elderly. Progress on both fronts has been hindered by Japan’s historic aversion to immigration, but there are signs that this may be changing. A government sponsored study of worker shortfalls in a range of industries is currently being conducted. So far it has suggested four areas where higher rates of immigration could be considered to boost the workforce: childcare, care of the elderly, construction and IT.

If progress on tackling Japan’s demographic headwinds largely remains elusive, it is far more visible in corporate governance reform, another key element of the third arrow. Before reaching any verdict on the success of corporate governance reforms, it is important to recall why they are so vital for Japan. For many years corporate Japan was insulated from capital markets by friendly cross shareholdings between companies. At the same time, boards had few genuinely independent, critical voices that were able and willing to challenge management. Moreover, management teams had very asymmetric risk/reward incentives, with limited upside from questioning internal vested interests.

Such weak governance and scrutiny of firms allowed poor capital allocation decisions to go unchallenged for many years. In some cases this led to substantial fraud, as at Olympus and Toshiba. More frequently poor capital allocation decisions led to a gradual erosion of shareholder value, as at Sharp, Kirin and Panasonic, where the Sanyo Electric writedown eliminated 20 years of net profit. Thus, poor corporate governance restricted return on equity at many companies, which in turn contributed to weak long term returns for Japanese equities.

The issue was not that Japanese firms were intrinsically unable to create profitable and high return business models, but that the mechanisms and incentives for reallocating capital dynamically had been neutered. Ultimately, this stemmed from a management view that de-emphasised shareholders as asset owners and prioritised corporate survival for the benefit of employees and society as a whole.

To recalibrate the thinking of Japanese management teams, their incentive structure needed to be radically altered.

The Abe-induced Corporate Governance Code, exemplified by the Nikkei 400 benchmark, has been a powerful tool in this regard. Composed of companies with a high investor appeal due to their efficient use of capital and investor-focused management perspectives, it puts pressure on firms to be included and shames those that fail to meet the entry criteria. For the first time there are social incentives for firms to improve their capital allocation and governance structures.

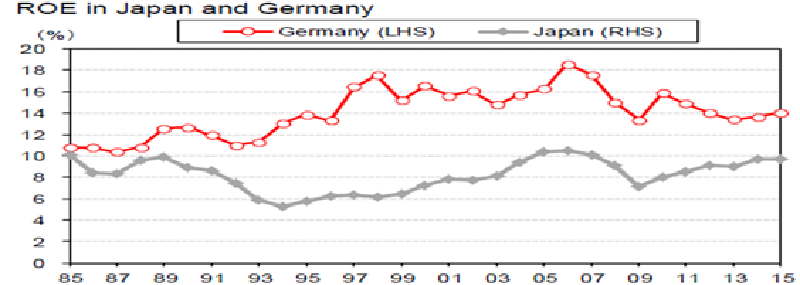

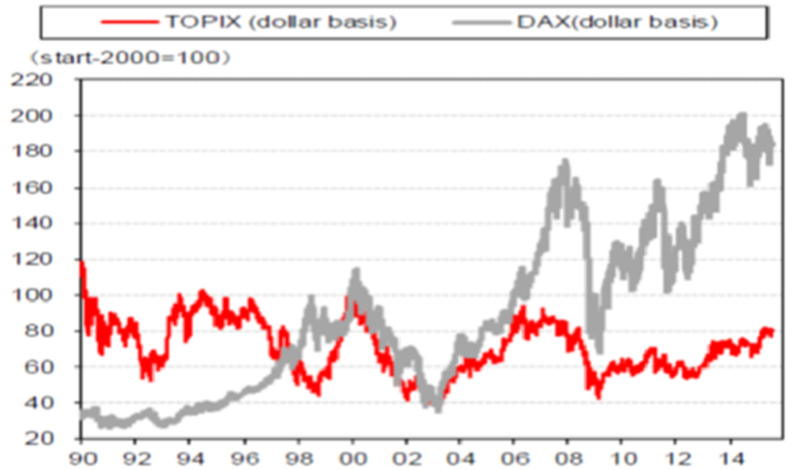

To assess the potential impact of such a change, it is instructive to look at Germany. Many of the problems facing Japan existed in Germany until the early 1990s, when the country embarked on a series of corporate governance reforms. As the VW emissions scandal demonstrates, Germany remains far from perfect, but it has undoubtedly made huge strides forward. Companies began to set ROE targets and routinely spin off non-core business units, with capital reallocated towards more attractive opportunities. Furthermore, financial cross shareholders were given tax breaks to unwind their equity portfolios, while labour market reforms made headcount reductions possible, both legally and politically. These changes boosted ROE, helping to drive shares dramatically higher. Over the same period, Japanese stocks fell 35%.

ROE in Germany and Japan

Source: Nikko SMBC

TOPIX versus DAX performance

Source: Nikko SMBC

As Germany clearly demonstrates, more active governance and corporate restructuring can enhance equity returns and cause share prices to rerate. It is therefore encouraging to see evidence of such improvements taking place in Japan.

We highlight some specific examples below:

The banks were expected to be key beneficiaries of the drive to reduce cross shareholdings in corporate Japan. Unrealised gains at the Mega Banks climbed from $1bn at the end of 2009 to over $6bn by the middle of 2015, meaning that they accounted for more than 50% of equity value. By realising equity gains, we believed the banks could remove equity volatility and allow management to pursue higher dividends and/or buybacks. In short, the banks could de-risk their balance sheets. The main problem is finding a buyer for these very large equity stakes. The most obvious candidate is a government entity, the Banks’ Shareholdings Purchase Corporation, which was founded in 2002 in the wake of the Asian Crisis to help facilitate non-performing loan deleveraging. To a certain extent our thesis of cross shareholding unwinding has been playing out, with the Mega Banks setting ambitious unwind targets that should be achieved over the next few years.

Seven & I Holdings board members rejected proposals by founding Chairman and CEO Suzuki to engineer his son’s succession. Suzuki resigned and Isaka, who heads the 7/11 CVS business, will become President and CEO. Independent directors and many staff were prominent in opposing Suzuki’s plan and supporting Isaka.

Nippon Telegraph and Telephone reorganised into wholesale and retail business units, reduced domestic excess capex, stopped investing in international telecom operators, and slashed its domestic cost base. The company abandoned top line growth objectives and focused on EPS growth through cost reduction and buybacks. Its shares have risen from Y1700 to Y5000.

Japan Tobacco closed several domestic factories, increased domestic pricing and acquired additional international businesses. Its payout ratio increased to 60% with additional buybacks. The shares have risen from Y1500 to Y4500.

Sony exited its Vaio PC unit, massively scaled back the traditional consumer electronics and mobile business units, and refocused on media and content assets. The shares bottomed below Y1000 and now trade at Y2700.

TDK recently announced the sale of its RF component business to Qualcomm for $3bn as management realised that the business was subscale. Unlike previous distressed transactions, the disposal was made when the business was performing strongly.

Hitachi has reorganised several of its Group Companies, merged Hitachi Transport with Sagawa, sold the HDD business to Western Digital, divested its LCD business to Japan Display and its semiconductor business to Renesas, and formed a joint venture with its power business and MHI. Management hope that a greater focus on social infrastructure (railways), medical, and care electronics will improve returns and margins. Hitachi’s board is frequently cited as an example of strong minded independent directors who hold the management team to account.

Amada, notorious for its disregard of shareholders and preference for hoarding cash, stunned the market by promising to pay out 100% of earnings and performing a large buyback. The cited motivation was a desire to be included in the Nikkei 400 ahead of its rivals. Amada shares bottomed at Y350 and now trade at Y1100. However, it must be said that the company still has some way to go to improve balance sheet efficiency. It retains >$1bn in real estate, $1bn in net cash, and $2.5bn in receivables and inventory versus sales of just $2.5bn.

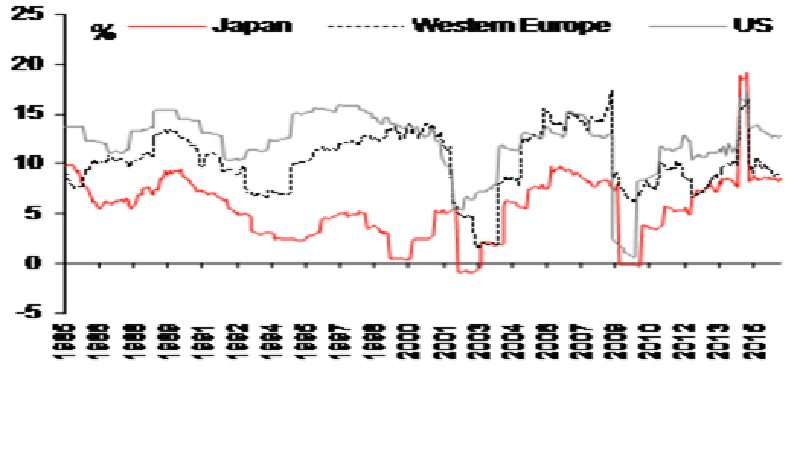

Beyond these specific examples, there is evidence to suggest that structural reforms are beginning to improve corporate performance more widely. Japan’s aggregate ROE has been rising for several years and, aided by the weaker yen, has been very similar to Europe’s in the current business cycle.

Return on equity

Source: Macquarie

Conclusion

Our research visit suggested that the appetite for monetary and fiscal easing remains strong. Both have the potential to dramatically improve investor sentiment towards Japan. That said, we must be cognisant of the diminishing returns associated with such easing, particularly as the transmission mechanism into the real economy remains severely challenged. Where we are most optimistic, and where we see the best evidence of progress, is the corporate governance reforms that are slowly enhancing Japanese equity returns. Despite improving corporate governance, the valuation of the Topix is consistent with a renewed recession or perpetual stagnation, implying that investors remain cautious about these reforms. In our view, this downbeat assessment creates the potential for substantial capital gains, making Japan arguably the most interesting play in G7 equities.

Nothing in this document constitutes or should be treated as investment advice or an offer to buy or sell any security or other investment. TT is authorised and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).